Convergence Factor: Micro

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 60: Skyglow

In my childhood in rural western Massachusetts, the night sky was embroidered with stars, and on summer nights, I would sometimes lie out in the yard, looking up. Watching for shooting stars, I contemplated the immensity of the universe and felt impossibly small in the most marvelous way.

Many years later, I laid down and gazed up from the floor of the Gobi Desert, a place with a sky so dark that the Milky Way practically slaps you in the face. There’s no missing it.

Last January, I stood out on my balcony, looking out over my neighbor’s garden, appreciating the moon and that particular smell of a crisp winter night. The view of the sky was limited, but it was something, at least, and there were still some stars to see.

With some effort, I counted eight.

Of course, living on the edge of the biggest, most populous megacity in human history1 means that light pollution is simply a fact of life. Outdoor lighting is important for various reasons, among them safety and utility, and while we could probably manage it much better, ridding ourselves entirely of its ill effects seems impossible.

One problem with light pollution is that it erects a semitransparent wall between us and the night sky, in between the finity of the human world on Earth and the infinity of the universe in which it floats. It interrupts our connection with an aspect of the natural world that has been important to humans for far longer than the span of recorded history.

In the Nabta Playa2, in what is now southern Egypt, is perhaps the oldest known astronomical observatory, dating back some seven thousand years. It predates the better-known Stone Henge by two millennia.

And it is possible that the cave paintings at Lascaux made reference to constellations3 some seventeen thousand years ago. Meanwhile, many of the distant descendants of the people who made these paintings, referencing arrangements of stars so very long ago, may not even be able to see enough of the requisite points of light in the urban night sky to be able to connect the dots today.

The history of homonins stretches back millions of years, and while early ancestors like Homo habilis may not have engaged in the paired acts of looking up and trying to understand the presence and movements of celestial bodies, it’s still been a notable activity for a very long time. Likewise, the ascription of mythological meaning to these things has been a universal practice for ages, though with innumerable variations between different communities, over vast areas, and over extraordinary stretches of time.

There are many ideas about when spoken language emerged, but if we take Chomsky and Berwick’s model4 as a point of reference for the moment, we can suppose that spoken language may have developed as long ago as two-hundred-thousand years. With this long a history, it is no surprise that storytelling is such a deep-seated part of human culture. And though nearly all the oral traditions of prehistory have been lost, a handful were preserved as civilizations adopted written language in the last three to five thousand years. Despite the general loss of knowledge and lore from prehistory, the tradition of storytelling has continued uninterrupted from time immemorial through to today.

Storytelling encompasses an immense range of themes and styles and purposes, having been used from very early on to entertain, to teach morality, and to explore the universe and our place within it.

And that last part, the exploration of our place in this world and the space that lies beyond, began with the act of looking up and wondering, searching for explanations.

That I can only see a handful of stars here, even on clear winter nights, saddens me because I like to observe them in their great plurality, rather than as simply the sad few that are bright enough to show through the skyglow and remind us, feebly, that they are still there. And I cannot say what the impact of this is in the broader context of culture and community in the twenty-first century, but I cannot imagine that this celestial disconnection does not come at a cost.

-

The ranking of cities and megacities is contentious, and the biggest, etc changes depending on which criteria are used, but if not the biggest in absolutely every evalution, Tokyo is at least nearly at the top, no matter how you look at it ↩︎

-

https://astronomy.com/news/2020/06/nabta-playa-the-worlds-first-astronomical-site-was-built-in-africa-and-is-older-than-stonehenge ↩︎

-

Business Insider: Archaeologists figured out that some of the world’s oldest cave drawings don’t just depict animals — they’re constellations of stars ↩︎

-

Berwick, Robert; Chomsky, Noam (2016). Why Only Us: Language and Evolution, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262034241 ↩︎

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can be awesome and support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 58: Meandering

Everywhere I have ever lived and travelled, Japan and far beyond, I have spent a great deal of time wandering aimlessly, exploring on foot, steadily wearing out shoes and making discoveries as I go.

Wandering enriches my daily life and teaches me something new every time I venture out. This includes teaching me a lot about wandering itself and how to do it well.

Let me share with you a mixed handful of thoughts on the matter.

Wandering should be an autotelic1 activity, done in the interest of doing the thing itself, with any other aims being strictly secondary. You wander because you wish to wander. It needs no other reason.

Assuming you have the time, getting lost is generally in your best interest, and frankly should be your goal at least sometimes. This is especially true in places you think you know well. Familiarity leads to lapsed attention, while the uncertain state of being lost amplifies it. When you get lost on purpose, you are necessarily in an open and highly receptive state of mind conducive to a positive experience.

Getting lost, furthermore, is the most effective way to get to know a place. Do it intentionally. Do it repeatedly. Do it well.

Whenever possible, opt for smaller roads and pedestrian paths. Choose the less-direct route and avoid going the same way twice in a row. Do not be afraid of repetition, however, especially if you make an effort to pay attention. There is always more to learn, more to see, and revisiting the same places can reveal layer after layer of detail.

You may wish to look for and navigate by mature trees rising above surrounding buildings, as they can help you find interesting places. These, differentiated from the trees under the “care” of the city (which often seem pruned in the spirit of eradicating any sense of love for nature), grow tall and full in their natural shape. They are usually found on the grounds of temples and shrines, though occasionally at parks, and sometimes within mysterious, walled estates.

If you find yourself at an intersection with a choice between roads that seem equal, choose your bath based on something specifically arbitrary. Choose the street with the sauntering cat, for example, or the one with the yellow house. Choose the one without the car that reminds you of your ex.

You can also be inventive in your navigation. Assign numbers to actions like turning left or continuing straight, or to the cardinal directions. When in need of navigational guidance, roll a die and follow the operation assigned to that number.

Similarly, assign actions and directions to the suits and ranks of cards in a deck, shuffle it, and let that guide you. You can even modify a Rubik’s Cube as a means of introducing purposeful disorder, which keeps one’s attention fresh, along with a playful sense of exploration.

Aside from saving interesting locations for later or getting directions when running out of time for wandering, try to refrain from using your smartphone. The experience is richer when unplugged, and your surroundings more interesting when you don’t really know where you are or where you’re going. Keep it, and your headphones, in your bag for later.

If you are able, walk rather than drive or ride a bicycle. It is slower, of course, but offers a number of advantages. Moving slowly lets you notice more about your surroundings. You are free, too, to pause and linger at will, and it costs nothing. Remember, too, that everywhere is walking distance if you have the time.

If headed somewhere specific and want to wander a bit on the way. consider getting off the train a stop or two before (or after) your intended destination and walking the rest of the way. Relatedly, much can be experienced if one chooses to follow the train tracks without riding the train, at least for a little ways. Development tends to be concentrated near stations, and in places like Tokyo, the areas farthest from stations begin to develop a feeling of existing in the slight vacuum of normalcy typical of interstitial spaces.

Finally, wander at all times of day and in all weather conditions. Can’t sleep at 3:00 AM? Go for a walk. Sleeting and blustery? Go for a wander. Taking a personal day? Go exploring when you’d normally be stuck in yet another pointless meeting.

Wandering is an act of exploration and an expression of personal freedom. Do it as often as you can. You will reap many benefits, I guarantee.

This post’s featured image is available as a print here. Patreon supporters get 50% off all prints in the print shop, and regular readers can still get 20% off using the coupon code “get20” at checkout.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 57: Glitch

Out walking somewhere in unfamiliar in Tokyo. About a quarter to six o’clock and the sun had nearly set. A warm day, it was still about twenty-five degrees and humid. In the third week of September, it was the sort of day that’s somewhere in between summer and autumn, stuck in a seasonal limbo between the two.

Everything felt slightly out of alignment and vaguely dissonant, though in a curiously pleasant way. The air itself seemed to hum.

Streetlights were switching on, as were lights on buildings all around. But something was strange, beyond the weird energy charging the air.

First on one apartment building, then another, the lights lining the long exterior walkways started switching on and off frenetically, as if controlled by the fluttering wings of so many electric butterflies flitting about in the evening sky.

The atmospheric hum grew intense and spread throughout everything. The world vibrated and sang for a brief time, and there was a sense of building pressure, as when one dives deep underwater.

It all remained suspended in this state for a minute or so, until some cosmic valve opened there was a sudden release of pressure.

The lights ceased flashing, the world back to normal. Everyone continued on with their Saturday evening as planned. Reality had glitched, and nobody seemed to have noticed.

NB: The following video documents part of the weird thing I experienced on Saturday, September 19, 2015

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 56: Music, Remembered

Music can do a curious and powerful thing. When it becomes emotionally significant, it has a way of tunneling into one’s mind and arranging details such that it, and its associations, become indelible.

It runs wires of interconnection between detailed remembrances of people, situations, and the emotions of the day. Music connects memories like a string of fairy lights that come on when a song flips the switch of spontaneous recollection.

In 2002, when I was in my third year of at Ohio University, I began corresponding with Kotone1, a Japanese woman a few years older than me who lived in Saitama and Worked in Tokyo. We got along well and quickly became close, exchanging emails and pictures almost daily. One thing we really bonded over was music, particularly rock.

Becoming close with her is probably what first led to my active curiosity in the possibility of someday living in Japan. The pictures she sent were captivating, as were all the details of daily life she shared. She gave me my first real insights into what life was like in the Tokyo area.

She’s who first helped me see Japan more as it is, and less as the idealized travel-guide version of itself that tends to dominate the picture when looking at the country through the dual lenses of tourism and fantasy.

Of course, what I remember most strongly from that time are the feelings that we developed for each other. We were sincerely into each other, in the manner and to the extent that two people can be purely through written correspondence.

I thought she was wonderful, but despite the closeness we shared for a time, the nature of things was such that our paths never intersected in the physical world. Oddly enough, though, I now live in Saitama City, very close to where she lived then, and she now lives in Chicago, not far from my old neighborhood.

I don’t think about that time all that often anymore. However, I remember it fondly, and all of it remains wrapped up in the music she introduced me to. Albums from bands like Guitar Wolf, Thee Michelle Gun Elephant, and The Pillows, and from artists like Tujiko Noriko.

It was music that connected me to a life and a place that were distant from my own, in which I was deeply interested. It was music that connected me to someone I loved. It was music that pointed at possibility. And it was music that made me feel more like the version of myself that I wanted to become.

When certain songs from then come on now, it all comes flooding back with great clarity. I remember sitting in my dorm room, writing to her and sending her every new picture. I remember the pleasant rush when a new email arrived from her or when she signed onto the instant messaging app we used. I remember listening to the music on my minidisc player as I walked across campus, our latest conversation fresh in my mind.

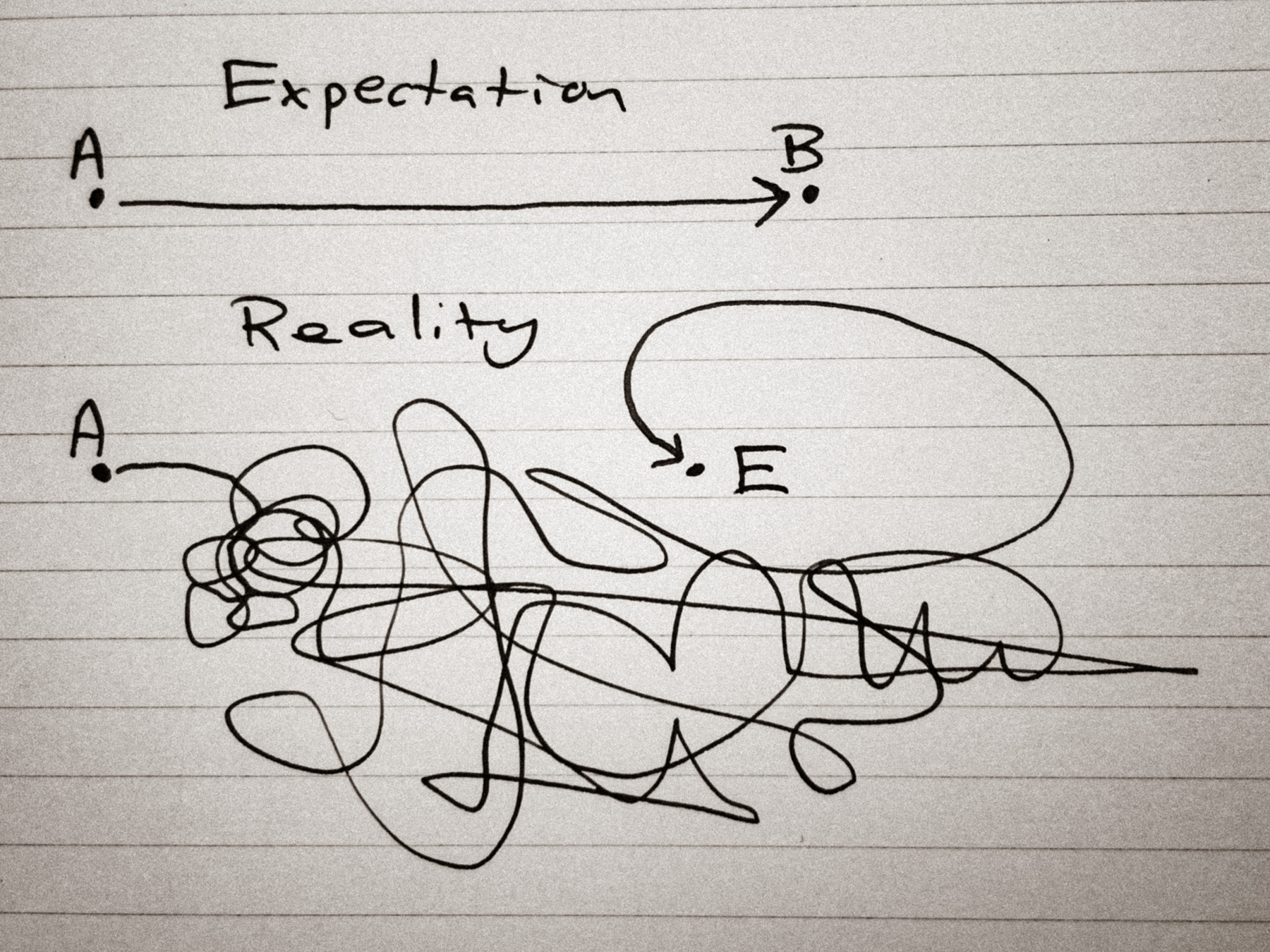

And I remember how it felt like all of this was changing the course of my life, steering me in the direction of Japan. Which, as it turns out, it actually was. The eventual shape of things turned out to be quite different from what I had hoped for back then, though. I’m an English teacher here, not a commercial photographer. I did not get my master’s degree at Tokyo Polytechnic2. She and I never even met face-to-face.

What I had originally wanted for and what actually happened are quite different. Which is fine, basically. Different isn’t bad, it just isn’t same.

It’s common enough for people to find themselves on diverging paths, and while the separation can be painful, sometimes we get to hang onto some of the good that preceded it.

Last weekend, I put on Gear Blues3 by Thee Michelle Gun Elephant and spent some time just inhabiting the memories and feelings it brought up, contemplating how it all had so much to do with where each of us wound up.

I’m happy for both of us, for the lives we now live, and I’m happy to have known her when I did. The memories I’ve kept are the good ones, and I can bring them back in high fidelity at any time. All I have to do is press play.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can be awesome and support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 55: Emergent Remains

For a weekend away, purely to have a change of scenery, we went to Chiba at the start of Golden Week1 one year. We rented a house and borrowed bicycles to ride to the beach. It was windy and too cold to swim, but we enjoyed a walk on the sand, and examined various objects we found.

Among other things, the wind had partially exposed the disarticulated bones of two dogs at the edge of a low dune.

How long had they been buried there? It must have been a long time. The flesh and fur had long since decomposed, and some disturbance had intermingled the skeletal remains. A disintegrating, salt-crusted leather collar remained half buried, vertebrae scattered around it.

Under what circumstances had they wound up there? One would like to think it was a loving, if illicit, act of burial. Perhaps those dogs loved the beach. However, the mind cannot not help but also explore other, less wholesome possibilities.

They were adjacent to other things emerging from the sand, in a way that made them seem especially lonely. Nearby, an old truck tire. A length of heavy rope. The cathode ray tube and corroded circuit board from an old television.

Nothing stays buried forever. No matter how deep in the sand, eventually things emerge. What happens after that, though, is anyone’s guess.

More than two years later, I have to wonder what the scene there is like now. Perhaps the sand has swallowed up the bones again, or they have been washed into the sea by a storm. There is no way for me to know, especially from a distance (though I wish there were).

-

A collection of national holidays primarily during the first week of May, details at https://www.japan-guide.com/e/e2282.html ↩︎

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan № 54: Resident Alien

They come out at night and look like alien worms, with glistening yellow bodies and fan-shaped heads. When it rains, they emerge from the ground and hunt. They are predators, preying on earthworms, insect larvae, and the like.

Bipalium nobile, a type of land planarian about which not a great deal is known. A relatively recent discovery, too, first having been documented in Tokyo in the late nineteen-sixties when a specimen was collected in the garden of the Imperial Palace. It was established as a new species a decade later.

Their bodies are especially long, measuring up to a meter in length. They are delicate, too, and easily break apart if one tries to move them or they are otherwise damaged.

Fortunately for the organism, it benefits from the same regenerative abilities possessed by many planarians. If bisected, the section without a head is fully capable of growing one, resulting in two separate, fully functional animals.

The first time I encountered them, at Shakujii Park in Tokyo’s Nerima ward, it did initially feel as if I were seeing something from a different world. Once the initial shock had passed, though, they immediately became fascinating.

Whenever it rains, I look for them and observe those that I find. Some days, they seem to be everywhere, though most people I’ve asked aren’t really aware of them.

But then, people are generally aware of nature being around them all the time. And it really is all around them all the time, even in the city.

If you pay attention, amazing creatures are everywhere, including strange, ribbon-like planarians hunting earthworms in the rain, looking like something straight out of a science fiction novel.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan № 53: A Reliable Bubble

While I can’t speak for anyone else’s habits, from time to time I find myself wandering to the convenience store simply because I’m feeling restless and can’t think of anything better to do.

Once, I even went during a typhoon. Admittedly, it was ill-advised, and in retrospect a bit risky, but it was fun. And, more importantly, it clarified something for me about the konbini’s1 role in urban life in Japan.

Among other things, it functions as a valuable oasis of reliability. A bubble of normalcy in an unpredictable and sometimes intense or chaotic environment.

When I went to the 7-Eleven while the typhoon Hagibis was making my building shift and groan with its gale, the walk to the store was reminiscent of Buster Keaton struggling to walk into the wind2, though with less comic flair.

When the automated doors closed behind me, I was suddenly in a very familiar scene, typical of any konbini run in the dead of the night. It was calm, and about as quiet as could be expected given the conditions outside.

One customer was looking at a magazine, another was standing bleary-eyed and listless in front of the onigiri. A clerk was stocking shelves.

The same elevator music as ever. The same door chime. The same fluorescent light making everything shadowless and tinged slightly green.

Stepping inside the store was like stepping into the eye of the storm. A temporary calm.

I lingered for a few minutes to appreciate the atmosphere and delay going back out, but even during a violent storm, it’s not really a place one remains too long. A place to stop by, but not a place to stay.

I purchased a tall can of Asahi Super Dry, a package of Bokun Habanero snacks, and a vanilla Coolish ice cream. The clerk wished me a safe journey home and I left.

Walking home involved leaning into the wind again, only this time leaning back as it pushed me forward. I couldn’t help but laugh at the absurdity of it.

Back in my kitchen a few minutes later, the window rattled and the exhaust fan spun strangely in the wrong direction. I enjoyed my 2:00 AM snack by myself in the dark, reflecting on the way that the brightly lit convenience store is often a calm and comforting place, even when the weather is fine, and how unexpectedly nice a part of daily life I consider that to be.

-

In Japan, the convenience store was originally referred to as a konbiniensu sutoa, now typically shortened to konbini. ↩︎

-

In his 1928 silent comedy Steamboat Bill, Jr., Keaton famously struggles against the wind of a cyclone. The sequence can be seen on YouTube here. ↩︎

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan № 52: Abandoned

The people of Japan are diminishing in number and shifting in location. Between 2000 and 2020, Japan’s population fell by about a million people1. During that same period, urbanization of the population rose from about 78% to just shy of 92% 2. What this means is that, of Japan’s roughly 126 million people, all but about ten million now live in urban areas.

These factors, among others, contribute to the surfeit of empty and abandoned houses littering Japan, most notably in rural areas. These houses are known in Japanese as 空き家3, read akiya, which directly translates as vacant house. The way things are going, Japan is on track to have a full 30% of its homes fall into that category in the near future4 .

They’re everywhere, if you look for them. I can think of at least four within a 100-meter radius of my apartment in Saitama City, and nearly twice that in the area close to my school. And the farther you venture from urban centers, the more common empty buildings become.

They are often easy to identify, especially those drowning in vegetation. This is particularly true of those engulfed in the same infamous kudzu5 that is so reviled in the American South. Whole properties disappear under draped green carpets of three-lobed leaves, blooming in June with purple blossoms that are shaped like pea flowers and smell like grape Kool-Aid cut with kale.

Sometimes, plants invade the interiors as well, with lush green foliage appearing behind kitchen windows, and stalks of bamboo bursting up through the floor.

Unfortunately, many have deteriorated well beyond the point of being unsalvageable. Many could be brought back to life with some effort, though, if anyone wanted to do the work. Most people are not so inclined, though a few are.

In Yokosuka6, a city about 60km south of central Tokyo, I met a man who fully restored a beautiful old house7 by hand, and stayed in an accommodation8 that had similarly once been abandoned. Both places were lovely.

The city is largely known for the US Navy base there, and near the base, the area is built up with high-rise apartment buildings, shopping malls, and the like. Out in the surrounding hills, though, there is a glut of vacant houses and empty storefronts. This is unfortunate for the city, of course, but more and more I’m beginning to see areas like this as places with a great potential for redevelopment, places where there is now an opportunity to build new communities and new businesses in a manner not feasible in locations like Tokyo, where property prices are extremely high.

My partner and I have decided to stay in our current apartment for another couple of years, but after that? I suspect that our next place will be one of these houses, and we will do the work to give an abandoned home a second life. Perhaps in Yokosuka, perhaps in Komoro9, perhaps in one of the declining hot springs towns where, who knows, we might even wind up with our own onsen. Wherever we go, though, and whatever we decide to do with that house, I look forward to the opportunity to reduce the number of abandoned buildings by at least one.

-

Source: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/JPN/japan/population-growth-rate ↩︎

-

Source: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS?end=2019&locations=JP&start=2000 ↩︎

-

View entry for 空き家 on jisho.org: https://jisho.org/word/%E7%A9%BA%E3%81%8D%E5%AE%B6 ↩︎

-

Source: https://asia.nikkei.com/Life-Arts/Life/As-Japan-s-empty-homes-multiply-its-laws-are-slowly-catching-up ↩︎

-

An interesting read on kudzu: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/true-story-kudzu-vine-ate-south-180956325/ ↩︎

-

A city in Kanagawa prefecture, view on Google Maps: https://goo.gl/maps/M2YRxGUPtr8qpz3z7 ↩︎

-

Some photos of the house can be seen here: https://www.facebook.com/karonojikan/ ↩︎

-

View on Air BnB: https://www.airbnb.com/rooms/39431685 ↩︎

-

A small city in Nagano Prefecture that we visited a few years ago and quite liked. View on Google Maps: https://goo.gl/maps/JruVL7z8JvqZpAFKA ↩︎

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan № 51: Communal Waters

A bank of shoe lockers, seventy-two in all, one with the door ajar and all missing their wooden keys1. It had been just inside the entrance, but no longer. Instead, it was exposed to the elements, making up one side of a fragment of structure, facing the large piece of torn-up ground where the rest of the building had once stood.

This used to be my local sento2. An unassuming public bath where I had once sincerely felt at home.

It was a third place3 for me and other regulars. Not home, not work. A place specifically neither, but still a place with a sense of belonging.

I didn’t feel it early on, but grew into it. It was its own little universe of experience, separate from everything else in my life. That separation made it a refuge.

Third places are important, but some are disappearing, public baths among them. This is one aspect of Japan’s declining social capital. Of course, the fact that most private homes now have bathing facilities largely obviates the need for the public bath in a purely practical sense. But the near-universal privatization of ablutions comes at a social cost.

The history of public baths goes back more than a thousand years4, and for centuries, it has been an element of daily life in Japan, providing a social function not replicated elsewhere.

This function has been on the decline for decades. Now, public baths regularly close and are torn down, taking their communities with them when they go.

Each of these places represents a whole little world of social interaction. A world that fades out of existence, starting the moment the bath closes its doors for the last time.

When I stood at the edge of the empty lot one night after my sento was demolished, I was struck by a loss of placefulness. The place that was there had vanished. Not just the building, but a place in which to simply exist and be comfortable in my own skin (and to share that experience with others doing the same). I could go to other baths, of course, and I did. But those establishments were different worlds, and there is simply no way to go back to a place that no longer exists.

-

Shoe lockers at baths are commonly locked by removing a flat key, often wooden, but also potentially plastic or metal. A good photo illustrating this can be seen in this article ↩︎

-

A type of communal bath house in Japan (read more on Wikipedia) ↩︎

-

An interesting concept that describes places other than home and work/school that fulfill certain social functions in community-building (read more on Wikipedia) ↩︎

-

Dogo Onsen in Matsuyama, for example, is mentioned in texts going back over 1,200 years (read more on Wikipedia) ↩︎

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan № 50: Ode to Fuzz

We sent the initial email while sitting on a bench in Besshonuma Park, hoping to meet an animal whose profile we saw on the cat shelter’s website. The reply came so quickly it was a bit eerie. A sign? We made an appointment for the following Sunday.

For the first several months of lockdown1, we had been at home together all day, every day. Aside from the grocery and an afternoon walk for some alone time, we were just at home. We’d gotten past the early difficulty of suddenly spending so much time together, but we also had a growing feeling that, especially with this being the shape of things for the foreseeable future, we wanted to make an addition to our life. We wanted a new member.

The shelter occupied the second and third floor of a large house near the station. Much of it was set up like a conventional shelter, with rows of large cages lining the walls of former bedrooms. However, many cats—those who had the health and disposition for it—were allowed to roam freely around the place, perching upon bookcases and crowding together on the couches like so many loaf-shaped throw pillows.

We went there to meet Anko-chan, a white-patched cat in the lanky, leggy stage of mid-kittenhood. She was very, very shy and climbed up onto a high shelf in a closet, where she was intent on remaining. We decided to give her a trial all the same. Before going home that day, though, we stopped by the living room and met the dozen cats relaxing there.

There, a magnificent beast appeared before us. He had long, orange fur, a fluffy chest, and a tail like a feather duster. He came up to me immediately and rubbed against my leg, informing me not only of how friendly he was, but also how soft.

We’d seen him before, actually. On Saturday afternoons, volunteers bring several cats to the train station to entice people to adopt. Once or twice, long before we’d decided to adopt a cat, he’d been there, and we’d remarked on how beautiful he was.

But when I saw him at the shelter, I was fully captivated. It was quickly put forth that we could have a trial with him instead, if I liked, and so all thoughts of that adorably long kitten went straight out the window.

One week later, he was looking out onto our balcony, and we began to get to know one another.

He’s a ragamuffin, we think, and he would have been an expensive kitten at one of those pet shops still so common in Japan, the kind with fancy puppies and kittens for five grand apiece. For unfathomable reasons, his original owners abandoned him and was a stray for a while. He was apparently found in our neighborhood, too, and I have to wonder if I ever saw him during his vagrancy.

While he was stray, he evidently had a hard time. He has FIV2 now, likely having been bitten by an infected cat during a fight. His left eye was also injured at some point, and now it’s always slightly irritated and watering. Eventually, someone took him to the shelter, where he was brought back to health, and where he remained, unadopted, for a couple of years.

Adult cats are harder to find homes for, especially those with health problems.

Tora came to stay with us a bit more than a year ago, and now we cannot imagine our lives without him. He has completely won over my girlfriend, who grew up with a dog and was unsure about cats. She’s crazy about him, and he clearly likes her much more than he likes me, which is saying something, as he definitely really likes me. I’m glad about it, too. He’s thoroughly convinced her of feline greatness.

He’s a funny cat, which I realize is a bit like saying that the Pacific is a wet ocean, but I mean it. Take, for example, that he almost always uses something as a pillow when he lies down. Sometimes it’s an actual pillow, such as on the couch. Sometimes it’s a book or a slipper. Sometimes it’s something that can’t possibly be very comfortable, like a camera or even, once, a set of hex wrenches.

When he meows, it’s almost always a breathy haaaaaaaaaa, and on the rare occasion he produces something closer to a conventional meow, it’s so tiny and high-pitched that it seems absurd to be coming from such a large cat.

He’s also big on touching. He likes to be in physical contact, too, and it’s not enough for him to lie between us in bed or next to us on the couch. No, he must also reach out a paw and place it gently on our arms, sides, or cheeks.

Tora is part of the family. He has changed my life for the better by being present, just as Mayumi has. I hope he lives a long time, and I hope that when we have children, they love him as much as we do. I can’t see why they wouldn’t, he’s very easy to love.

Figuring out what works in life can be rather like assembling a puzzle that requires you to go and locate the individual pieces out in the world before trying to fit them together. This fuzzy puzzle piece fits perfectly into our lives and into our happiness. I’m so very glad we found each other.

If you’re considering getting a pet, please consider adopting an adult animal from a shelter. Adult cats and dogs are just as wonderful as younger ones, and at much higher risk of euthanasia because they’re harder to find homes for.

And if you’re in/near Saitama City and want a cat, I can gladly recommend the shelter we got Tora from. Their site is at http://www.machikado-jyoto.com/sp/index1.html

Finally, if you’re on Instagram and want to see more of Tora, he has his own account there. Which I update once in a while. Check it out

-

It should be noted that, in Japan, there was never any true lockdown, in the sense of movement being restricted. Under the Japanese Constitution, that manner of limitation is impossible. The state of Emergency, however, did lead to many companies switching to remote work or closing up for a while. ↩︎

-

Feline immunodeficiency virus, a retrovirus similar to HIV in humans, though it tends not to be deadly, and infected cats can still live fairly long and healthy lives. ↩︎

Somewhere in Japan № 49: Hushed

How is it that the quiet of the night differs from one place to the next? You’d think quiet is quiet, but it has varieties, much in the way that sunlight takes on different nuances in different parts of the world.

I notice it most late at night when I’m writing in bed, a pressing idea keeping me awake.

The wind outside gusts sharply. The neighbor’s garden, an overgrown expanse of green just beyond our balcony, sits silently until the wind calls upon every leaf and branch to rustle at a perceived volume that makes one wish for a stronger word to describe it.

In relative terms, it’s a cacophony, and it seems so because it has otherwise been so tremendously quiet that minute sounds are magnified.

Quiet enough that I can clearly hear the rhythmic clacking of trains passing more than a kilometer away. Not the sounding of the horn, just the rolling of smooth wheels on well-maintained rails, reduced to a whisper over the intervening distance.

Quiet enough to hear the soft footfalls of some unknown animal threading its way through the tall weeds behind the building. When I try to picture what it might be, something about the rhythm of the steps brings to mind the masked palm civet I’ve seen down there before.

Quiet enough that even the scratching of my fountain pen nib on the paper seems so noisy that it might wake my partner. The cat is stretched out between us, and I instinctively hold my breath if I move just a little too much and he stirs. His purr is also quite prominent in this hushed environment, and it starts up automatically whenever he is disturbed.

He usually goes back to sleep, though, and she rarely wakes. I go back to writing, often wishing I had chosen a quieter pen.

The main home for this blogging project is over at Somewhere in Japan, where I hope to expand my activities into a greater variety of creative forms this year and for years to come. I want to do more, and to really make that happen, I can't do it alone.

To that end, I have started a Patreon where people can support this project. There is only one tier and it's cheap, at just $3 a month. It's enough, though, that if I can get a dozen or so people to support the project, it'll make a big difference. Check it out at patreon.com/somewhereinjp

Thanks!

Somewhere in Japan № 48: Lineage

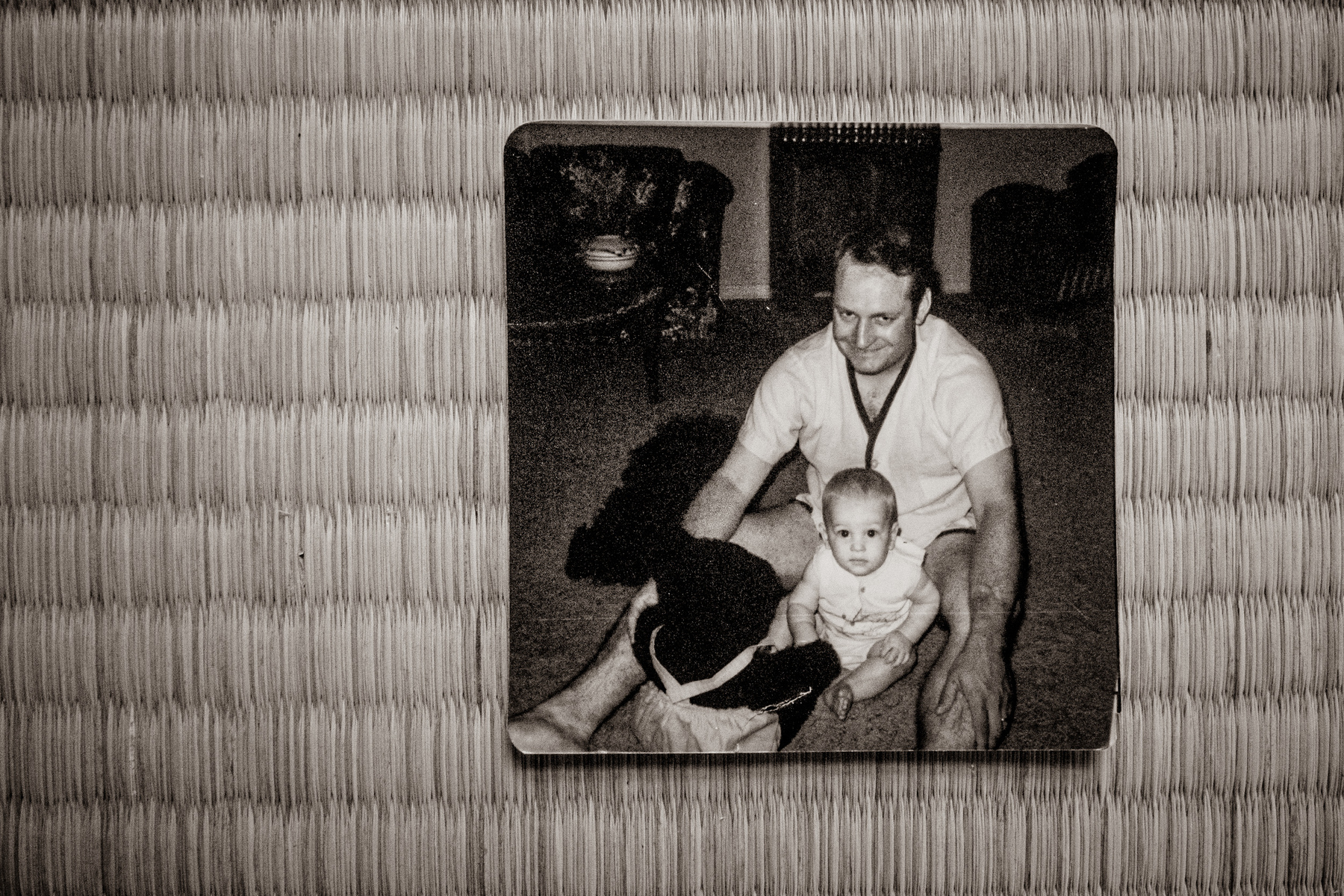

A photograph, 10cm square with rounded corners. An interior scene. In the dim background, an oval coffee table in front of a blue floral loveseat, both adjacent to a bookcase and a wooden cradle.

The painted edging on the table and the gold embossed text on the spines of the encyclopedias gleam in the shine of the flash cube fired from the top of a Kodak Instamatic.

A man sits on the floor wearing summer pajamas. Between his legs sits an infant, its arms and legs so chubby with baby fat that it has creases mid-forearm. A toy bear sits in front of both of them, and a black-haired dog reclines behind.

Long after the baby has grown into a man, he sits on a bench in a park in Japan, ten thousand kilometers and thirty-nine years from Lubbock. A warm summer evening. He is thinking about life and the shape it takes, his own path, and where to go next.

At about eight thirty, another man arrives at the park on a bicycle with his daughter, age three. They play together on the nearby play structure. He catches her, bubbling with laughter, at the bottom of the slide. She chases him around the fiberglass hippopotamus, then hides in its cavernous mouth, failing completely to stifle her laughter.

It is late for her, and so they do not stay for long, but as long as they are there, they are fully saturated with joy and sprinkled liberally with sincere affection. One would be hard pressed to find a better example of a father and child who clearly love each other.

Having watched all this, the man on the bench removes the small square photograph from inside the back cover of his journal and looks at it somberly. In it, he is the child, but more than anything, he wants to have a photo like this of his own, in which he is the father.

It feels so far away, though. Almost impossible with his circumstances. She’s getting older, too. They don’t have all the time in the world. All of it makes him feel hollow and sad.

At very least, though, he knows that if ever there was a good reason to work hard, improve his employment, and get his life in order, this is it. Do it for the sake of the family he longs to have.

The main home for this blogging project is over at Somewhere in Japan, where I hope to expand my activities into a greater variety of creative forms this year and for years to come. I want to do more, and to really make that happen, I can't do it alone.

To that end, I have started a Patreon where people can support this project. There is only one tier and it's cheap, at just $3 a month. It's enough, though, that if I can get a dozen or so people to support the project, it'll make a big difference. Check it out at patreon.com/somewhereinjp

Thanks!

Somewhere in Japan № 47: Still Smitten

35°44’23.2296"N, 139°36’5.5074"E

All I knew about her before we met was what the language-exchange service had told me: office worker, female, age 30-39, wants to learn English conversation, wants to teach Japanese language and culture. Accompanying message: “I have an interest in your profile. Yoroshiku onegaishimasu.”

I didn’t know what to expect or who to look for in front of the café where we’d agreed to meet. When an attractive, well-dressed woman asked if I was David, it caught me off-guard.

She says I was very serious and businesslike that day. Which makes sense, as we were meeting for language purposes, and I was used to teaching a lot of private lessons back then.

I was single, but really didn’t want to be, and as we were leaving a while later, a thought bubbled up from my subconscious. Wouldn’t it be something if I wound up with her? I kept this to myself, of course. She was there to practice English, not to be hit on.

All the same, about a year later, I asked her to meet me at the park one Saturday evening. And there in the park, on that warm summer evening, under the indigo sky and lamplight, I gave her a ring and promised to love her forever.

That was June tenth, 2017. Four years ago today.

We got along well from the start and soon began hanging out. After about six months of meeting and going out as friends, it naturally evolved into dating. She was funny and smart, kind and interesting. She was also very, very cute. I was smitten.

A few months after that, I had a realization that hit me like a meteor. It was suddenly the undeniable truth, the most obvious thing that could possibly be: it was her.

Her as in her, the person I wanted to be with for the rest of my life. Her, the person I wanted to have a family with. Her, the woman who finally made sense of that saying that always sounded suspect to me before that. When you know, it turns out that you really do know, and I tell you what—I knew.

I knew it then and I still know it, only now it’s backed up by the added experience of year upon year of being crazy about her. I remain smitten.

I love the way she stretches, catlike, in the morning. I love the way she is sometimes overcome with unrestrained, guileless excitement, like the first time we went away together, when she ran to the water’s edge in Kamakura, giggling all the way.

I love the fact that she reads more than anyone else I’ve ever known, and that she always has the maximum possible number of books reserved at the library.

I love that she’s sexy, but even more that she’s silly. I love her for her kindness, patience, and good humor. I love her for the person she is.

I don’t really know why she loves me, but I am grateful that she does. My love for her is such that it enables me to work harder and hold myself to a higher standard than I could in her absence.

That I get to spend the rest of my life with her, with my favorite person in the world, makes me feel incredibly lucky.

Somewhere in Japan № 46: Offerings

35°44'37.7514"N, 139°36'51.7644"E

In one hand, the figure holds a staff, used to force open the gates of hell in the course of liberating souls. The standard iconography usually has him holding a light-bearing jewel in the other hand, but here he holds an infant instead. Two more stand at his feet, tugging at his robes.

This is Jizo Bosatsu, a bodhisattva1 known in Japan as a guardian of children.2

Years ago, on a gloomy, wet Saturday in Tokyo, I visited a shrine to him on the grounds of a temple.3 A life-size statue, described above, stood on a plinth, flanked by thirty-four smaller Jizo statues. In front of them all were laid a number toys that sagged with extra weight from the rain. They had been left as offerings, and many appeared to have been there for quite some time.

There was no way to know who had left them or why. No way to know if the offerings had been made for children who had been saved, or lost, or perhaps hoped for by would-be parents.

It’s possible that some small portion of them were offered in thanks of something good, but one knows at heart that most would have been left in solemn circumstances, at best, and at least some of the toys moldering under the low clouds that day were relics of loss, offerings of the bereaved.

Sources referenced

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K%E1%B9%A3itigarbha?wprov=sfti1

-

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is one who has achieved enlightenment, but has also vowed to save all beings before becoming a Buddha ↩︎

-

More thoroughly: a guardian of children, the weak, travellers, lost pregnancies, and also the removal of splinters. More on Wikipedia ↩︎

Somewhere in Japan № 45: Repeater

35°39'16.401"N, 139°45'26.1138"E

Occasionally, I board the Yamanote Line in Tokyo, only to get off again at the same station a while later. I do this for my own enjoyment. This line runs in a loop and has a ridership of three or four million passengers per day. So many people, but I don’t think many are there just because they feel like it.

It is not especially fun, as trains go. It’s often extremely crowded, and it stops every minute or two. So why would I choose not only to board the train when I don’t really need to, but also remain in my seat for at least one full trip around the loop?

To see what happens, for one thing. What happens within the train and every time the doors open, yes, but also what happens to my perceptions of the train itself.

The longer you stay on the train, the more it feels like a place unto itself, rather than a means of conveyance between stations. After a while, a shift occurs. Station by station, the liminality mostly drains out of it.

For nearly everyone on the train, it’s just a long metal tube you ride in until getting to the desired location. That’s it. But for the deliberate rider, the means of transportation becomes the destination. A curious destination, too, in that its location is always changing.

One trip around the Yamanote Line takes about sixty-four minutes. The most I’ve done in one go is three complete loops.

Something about the experience changes once the stations begin repeating. Until then, it’s mostly like any other hour-long ride on a local train. When you see the same places for the second time, or especially the third, a curious feeling arises.

Just as repeating words enough times reduces them to strings of strange sounds that no longer feel closely associated with any particular meaning, riding a train in a loop eventually leads to a disassociation of the experience from our original perceptions and assumptions.

And once it is at least partially disassociated in that way, the experience is free to take on extra dimensions and nuances.

So after thirty or sixty or ninety stations, all while sitting in the same seat and seeing the same places roll by repeatedly, everything—the train, the stations, and even you—emerges looking and feeling at least a little different.

Like today’s featured image? A color version is available in my print shop, along with a variety of other images. And right now, you can get 30% off your order with code “get30”

Somewhere in Japan № 44: Shuttered

35°43'33.4668"N, 139°31'24.5172"E

It’s difficult to know which of these buildings are truly vacant and which simply look the part. All of them once contained some kind of business, as well as the attached housing of the shop owners. Japan is full of shuttered shops like these.

In many cases, the people running these businesses reached retirement age without any heirs, or at least without any who wanted to take over the business. And so the businesses didn’t fail, but nor did they continue. The shutters came down, and the customers stopped coming, but life continued inside.

Whether vacant or occupied, eventually these places wind up looking the same. Rusted steel frames hang above doors, festooned with the tatters of former awnings. Signage is largely peeled and corroded into near-illegibility, if it’s even still there. Often, the signs have disappeared, and all that’s left to show they were ever there is an empty frame with broken lightbulbs or a blank rectangle on a wall, outlined by faded paint or a halo of grime.

The mail slot might also be clogged with a thick mass of old letters and bills, fused together like sedimentary stone after years of exposure to rain.

If there are plants in front, and there often are, these can give good clues regarding human presence. Do they appear cared for, even a little? Or are there just a few stragglers remaining? The hardy, long-term survivors resilient enough to persist untended in plastic pots year after year.

Near my home stands building occupied by four shuttered businesses. On either end, faded signs still hang. One shop had been a Chinese restaurant and the other a soba place. These both appear not to have had a living human in them for at least a decade. The other two still have people in them, though you have to pay attention to find evidence of this.

At one, the shutters come up partially now and then, just high enough for a stooped woman to emerge and water her plants or pull her cart to the nearby supermarket. In the front room of the now-defunct shop sits a bicycle of indeterminate color, the tires of which are flat and crumbling, flaking little bits from the sidewalls onto the floor.

At the other shop, the plants are mostly dead, and the shutters never seem to move. Once in a while, though, a dim lamplight adds a feeble glow to an upstairs window. This is the only clue that anyone is inside.

Recently, a thin man with thick white hair emerged from another apparently empty building nearby, just as I was passing. He said hello, and I tried not to look too astonished by his presence. After more than three years in my neighborhood, I had never once seen a single sign of life there, and certainly hadn’t expected him to appear.

Since then, I have felt far less confident about which local buildings are actually empty. Those that are vacant interest me, but not as much as those in which people still pass their days, quietly and all but invisibly. And in those cases, it’s the unseen lives I find most interesting of all.

Like these posts? Get them directly in your inbox by signing up at Somewhere in Japan using the form at the bottom of the page. You can also follow my blogging project on Instagram.

Somewhere in Japan № 43: The Summer Trope

35°44'7.3536"N 139°36'50.4606"E

Cumulonimbus clouds, gaining height in the haze-attenuated blue of the late-summer sky, growing taller as the afternoon passes. Trees cast stark shadows on the dusty ground while wearing the dark green hues of August. Later, it will rain, but for now the sun inundates everything, just as the aggregate calls of hundreds of cicadas saturate the air.

This is the peak of the season, a crescendo of heat, humidity, and natural noise, a fever pitch of seasonal intensity preceding the prolonged transition into autumn’s gentler tones.

This period lasts for but a handful of weeks. And despite the oppressive weather, it has a particular appeal, an atmosphere of sufficient aesthetic weight to make it a preponderant cultural trope.

Take, for example, the way it is commonly used to set the summer scenes in animation. The skies and the clouds, the sun-drenched trees and the deep shade beneath them—all the elements are there. Even the sounds of specific species of cicada are used to evoke particular moods.

Hyalessa maculaticollis, min-min zemi in Japanese, with its name containing the onomatopoeia of its own call, makes a sound easily associated with the intensity of midday heat. Tanna japonensis, on the other hand, called higurashi, calls mostly in the evening, its melancholy song echoing the ephemerality of both the season and of its own life.

It is a season for the seaside and the mountain stream. A season for eating ice pops while walking over the blistering asphalt of country roads fringed with green foxtail, the green of which has begun to fade to brown.

It is a season in which all is briefly held in suspension, the conditions and temporalities informing the impermanence of everything, imploring us to appreciate what we have while it’s still with us.

Recommended links:

- The sound of the min-min zemi

- The sound of the higurashi

- A video about the use of these sounds in Japanese animation, featuring some samples from different series

Sources consulted:

- https://features.japantimes.co.jp/cicada/

- http://yabai.com/p/3326

- Hyalessa maculaticollis on Wikipedia

- Tanna japonensis on Wikipedia

Somewhere in Japan № 42: Chicken and Beer

35°43'46.0014"N, 139°43'2.1828"E

It was just before Christmas and my friend and I were hanging out in Ikebukuro, an area on the north side of Tokyo. We had been wandering around aimlessly and were outside a convenience store when a man approached us.

He was an older man, thin and a little shorter than me. He had white hair and a scruffy, nicotine-stained beard. Given that we were in an entertainment district, I half expected him to be promoting a hostess bar or pink salon, but it quickly became clear that he just wanted to talk. He asked many questions and seemed sincerely interested in us.

After just a few minutes of conversation, he suddenly excused himself and went into the convenience store, emerging a little later with a piece of fried chicken and a beer for each of us. After a few more minutes, he said goodnight and went on his way.

The entire experience was quite brief, and though it was certainly a pleasant encounter, it was also somewhat bewildering. Who was he? Why had he chosen us to receive his kindness?

It’s not the only time something like that has happened to me. At least a dozen times in the last six years, strangers have appeared out of nowhere to strike up a friendly conversation. Occasionally, they’ve also offered food or drinks.

Tokyo can feel like a very cold and impersonal place. In fact, it’s easily the loneliest place I’ve ever lived. But there are kind people around, no matter where you go, and sometimes they emerge from the woodwork to buy you a snack and give you a reason to smile.

Like these posts? Get them directly in your inbox by signing up at Somewhere in Japan using the form at the bottom of the page. You can also follow my blogging project on Instagram.

Somewhere in Japan № 41: An Impossible House by the Sea

35°43'51.456"N, 139°36'36.0714"E

There is a derelict house in my old neighborhood that surfaces in my dreams now and then. In reality, it is in Tokyo, boarded up and sitting behind a yard overgrown with tall grass. It is surrounded by new houses and young families.

When it appears in my dreams, however, it is instead in the countryside, by the sea. It is not sealed with sheets of plywood, nor is it falling apart. The windows and doors are thrown open for the air to flow through them. It is in beautiful condition and filled with activity.

The grasses of the overgrown yard remain the same, however. Soft and coming up to mid-thigh when walking through them, soughing gently in the late afternoon breeze. And instead of ending at the street, they stretch off towards the ocean, swaying as waves break below the bluff.

Here, in the dreamscape, is where this vision begins mixing with elements from other memories. The grasses in that lot in Nerima transition into the grasses I stood in as a child at eight years old while travelling in Nova Scotia with my family. In this way, my mind derives the Pacific from the Atlantic while moving a bit of Canadian coastline to Ibaraki, and all to give an impossible new life to an old house that deserved better.

I can’t help but to wish it were real, and also to wish it were mine.

Somewhere in Japan № 40: Celluloid Time Machine

Rainy season has come early this year, and so has my annual effort to catch up on my undeveloped film. I’m not sure how many rolls there are, but I’d guess about fifty rolls. This isn’t too bad, at least compared to ten years ago when it was close to two hundred, but still far more than it should be.

Most of it is recent, shot within the last year, but mixed in are a handful of stragglers from much longer ago. Sometimes these rolls are just misplaced for a while, and sometimes I put them off again and again because they require special development that I just don’t feel like dealing with. Others seem to have come through some kind of time warp.

When hanging film to dry last Sunday, I was surprised to notice pictures of an ex-girlfriend on one roll. This was the ex who once inspired panic attacks whenever I saw someone at a distance who even resembled her even a little. The ex who I left when I moved to Japan by myself to start over.

After leaving her, I deleted or destroyed almost every photograph of her I had. There aren’t many left.

Part of me wanted to throw the whole strip of film in the trash and forget I ever saw it. And I might still excise those particular frames, but jettisoning the whole thing seemed unfair to the other photographs. I realized, too, that on every other roll of film I had hung to dry, there were snapshots of my partner, Mayumi, and that made me feel better.

Had I not spent those years with my ex, I wouldn’t have arrived in Japan when I did. Had I arrived at a different time, I probably wouldn’t have met my partner. Thankfully, I did.

The joy I have with Mayumi firmly outweighs the suffering of past relationships. I adore her.

I have zero interest in having my ex, or her image, in any part of my life. Still, I should be grateful that the experience of being with her, painful though it was, led me to where I am, and who I’m with, today.

Somewhere in Japan № 39: Doing Nothing

35°29'13.3908"N, 139°44'35.4582"E

There are two kittens in the bushes. Both are striped, though the smaller one is half-covered with splotches of white fur, as if it had been interrupted partway through repainting. They’re skeptical but not unfriendly, and warm to you the moment food is offered.

Just beyond the shrubs runs a long fence. On the other side of the fence is the bay.

Fishing rods hang out over the water, some of them attended and some of them not. There are few women, but mostly men, and most everyone is over sixty. It’s clear that, for most of them, fishing is only a pretext to come here and enjoy this warm summer evening.

There is not much to do besides watch the water and make small talk. The nearest people are a man and a woman, seemingly old friends. Sitting on upturned buckets, they are drinking 9% canned cocktails and smoking cheap cigarettes.

The man breaks off a bit of his rice ball and tosses it towards the bush. The kittens emerge and briefly vie for it before the larger one runs off with the food in his mouth.

At this, the friends laugh easily, in the way one only can when doing nothing. That is, specifically doing nothing, which differs from not doing anything. The former is a deliberate act, the latter is incidental.

This is a good place to come and do nothing, with or without the cover story of fishing. It is a place to go and a place to stay, if only for a little while. Later this evening, everyone presently lingering will have gone home, and the cats will have it all to themselves.

Somewhere in Japan № 38: As-Is

Many people say they love Japan, but really only love a particular, highly distorted concept of it. They don’t realize it, and they don’t like it when you point it out. Often, they are also disappointed when they come here and realize that Kyoto isn’t all geishas and temples at sunset, that Tokyo isn’t a neon cyberpunk wonderland, and that anime isn’t real life.

Unless, of course, they’re so completely committed to their expectations that they just see what they want to see, anyway, and reality goes unnoticed.

A big part of the problem has to do with the most popular sorts of images people see. These are the over-saturated, cherry-picked views of Japan that dominate much of the internet. If you look around at Japan-related feeds on Facebook, Instagram, or Reddit, you’ll quickly see what I mean.

It’s very common and very human to hold idealized, romantic fantasies. We all do it, and within reason it’s fine. It’s often taken to an extreme, however. These images express a fantasy about Japan some people want to believe in, and the depiction is about as truthful as a bad made-for-TV movie that is based on a true story, but only technically, and only just barely.

What good do these fantasies do, for us or for what we love? When we prioritize fiction over fact, we don’t really love what we claim to. We only love the idea of it, and an inaccurate idea at that.

Just as the overly retouched images in fashion magazines distort perceptions about bodies and beauty, popular images of Japan distort what people think of this place and its people.

If you really love something and believe in it, then kill off your fantasies. Let the truth stand on its own. Love it as-is, for what it is. And if you think you love Japan, that’s great. Just make sure you love it for its own sake, not for what you expect it to be.

Somewhere in Japan № 36: Dead Fountains

35°47'10.2438"N, 139°17'0.693"E

Admittedly, I have no numbers to back this up, but I would still put forth (with confidence) that Japan is the world leader in disused fountains. The local park where I spend so much time has two. And yesterday, I sat on a bench next to a fountain that the map still shows as being something with water, when in fact it has clearly been out of use for a very, very long time.

In decades past, they usually built public parks with fountains and other water features, some of them quite ambitious. Perhaps because the bubble economy burst long ago, and perhaps because public sentiment shifted away from the value of moving water in urban park settings, now they nearly all sit derelict, dry and clogged with leaves.

Rare is the fountain that still works. Common is the fountain that, rather than bubbling and shooting wet jets skyward, is instead festooned with cautionary signs warning children and others not to play on them.

But why shouldn’t they play? If they’re not going to be brought back into use, and it seems clear enough that they mostly aren’t, then why not at least convert them into something fun?

The one I sat next to yesterday, for example, was broad and flat like a fifteen-meter dinner plate with an upturned edge. Fill it with sand, perhaps, or carpet it with sod. Let local artists make a mural of it.

One way or another, why not do something, anything, to change these concrete structures littering the country from sad reminders of a lost belief in joy-focused infrastructure into something that’s at least a little fun again?

The bureaucrats would, I’m sure, trot out a variety of reasons why nothing can be done about the sad state of Japan’s public fountains. But I don’t care. I believe in public spaces, and I’d like to think that at least some of these fountains will one day be filled again, and the rest can still be somehow enjoyed.

Somewhere in Japan № 35: Open Wide

Breeze and birdsong alike flow liquidly, languidly into the apartment through windows thrown open wide to invite the atmosphere in. In the spring and fall, they’re kept open as much as possible, closing them only when it rains heavily enough to start coming in.

In the summer, the apartment is an oven. By midday it’s usually hotter inside than out, and stays that way even after the sun has set.

In the winter, the opposite problem. Waking up on January mornings, I watch my breath form brief clouds in the air above the futon, where I consider how warm I am under the quilt and how cold it is in the room.

In the heat and in the cold, the problem has the same root: single-glazed windows and a dearth of insulation. This is common in much of Japan, especially in older buildings like ours.

There are interventions, of course. The aircon cools and warms enough to take the edge off, but the effect is fleeting, with thin walls doing little to prevent the inside air from reverting to the outside temperature in short order.

So in the summer we run the fan and cover the windows with sunshades. And in the winter, we bundle up and spend much of our time either at the kotatsu or in front of the space heater.

But in the spring and autumn? These seasons are joyfully easy, and we appreciate that nothing special must be done for comfort. In fact, the most comfortable course of all is to do nothing but let the air flow through our home unencumbered, windows open wide.