Convergence Factor: Micro

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 88: Oh, an Earthquake

My aunt saw my kitchen on the news. In a segment broadcast on her local NBC affiliate in the USA about a recent earthquake in Japan, a short clip showed my kitchen shelf swaying and some instant ramen falling from the top of my refrigerator.

Three different TV networks had messaged me on Twitter to get usage permission after I shared the video. It wasn’t a particularly interesting clip, but it was posted just a few minutes after the quake, and news services like what’s fresh.

The earthquake itself didn’t last all that long, but I was able to capture most of it because I started recording the scene within a few seconds of it beginning. My immediate thought was to record, so I did. I had no fear during that earthquake, and frankly never have in any that I’ve experienced. Which some people have told me is strange.

Fear is a natural and reasonable response to an earthquake. The ground decides to move of its own accord, shaking everything on its surface. People may be injured or killed, buildings and their contents damaged or destroyed, and there is absolutely nothing anyone can do about it as it happens. We, as weak little humans, are entirely helpless to stop it. It’s scary.

So why am I always so calm during these events?

Part of it could be explained by compartmentalization. In emergency situations, some people automatically become especially focused and rational, with any related response not landing until later.

Another part of it is perhaps that, after living long enough in a place where smaller earthquakes are a regular part of daily life, a person simply gets used to them (to whatever extent a person can become accustomed to the unpredictable).

With earthquakes, though, there’s also an odd comfort in having absolutely no control in the situation. You have to simply wait to see what happens. Fear and panic do nothing to help.

For whatever reason my brain is wired such that a fear response never enters the picture.Not with earthquakes, at least.

In social situations, like asking someone out on a date? Absolutely terrifying. But when my home is suddenly lurching about and I have no idea if it’s just going to be a few things falling from shelves or if the building is going to collapse with me inside it? Absolutely calm and focused.

It is useful, in that I am a good person to have around in an emergency situation. It occasionally leads others to regard me with suspicion, though, and some have even taken offense to my finding earthquakes more fascinating than frightening, as if it is innately disrespectful to earthquake victims to not be automatically terrified.

Eventually, I’m sure I’ll be here for at least one especially large quake, something of a scale that is truly life-threatening. And when it happens, I hope that my reaction is the same as usual, so at least I can document and be of help in the following response period. Not any time soon, though, I hope. As captivating as the smaller earthquakes can sometimes be, at least for weirdos like me, I’m perfectly content for the big one to remain indefinitely in the future.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email.

And if you like what I’m doing, please consider directly supporting this project for as little as $3/mo on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 87: A New Bath to Call Home

A bath at home is well and good, but a bath at the sento1 is a thing apart. Something social, even if you don’t talk to anyone aside from the proprietor. And if your visits become a regular occurrence, the importance of the sento in your daily life can become significant. It may contribute to a greater sense of home or belonging in your local community. The sento may even become a third place2, which is of particular value when third places are rapidly declining.

The last time I really had access to a public bath that filled that function for me was years ago in Tokyo. But that bath closed down and was demolished, and then I moved away to another city.

Since then, there has been a sento-shaped void in my life, although there are two public baths within easy walking distance of my apartment.

I visited the closer one of the two not long after moving, but only once. At that time, my depression was worsening, leading to a sort of turning inward and retreating from the outside world, so I never went back, pleasant though it was.

Then the pandemic struck, making me wary of going. As relaxing as a trip to the bath can be, the prospect of potentially catching a deadly illness along the way reduces the overall appeal.

But with new infections now very low, a full vaccination under my belt, and the weather finally cooling off, the conditions are prime to return to the sento. A good time, even, to make a regular habit of it.

So last Saturday, we headed off to the other local bath, where she had been but I hadn’t. We prepared our towels and bathing items and walked there on quiet back streets.

We left our shoes in the lockers at the entrance, taking with us the slotted wooden blocks that function as keys. Stepping inside, it was immediately comfortable, and we were greeted by the familiar smell of the bath, the warm smile of the attendant, and the sounds of splashing water. The clattering of plastic washbowls and low stools on the tile floor echoed off the high ceiling of the bathing area.

We paid our fee3 and parted ways—she to the women’s side and I to the men’s.

The locker room, like everything else, was well worn from decades of continuous use. nearly everything about this establishment could comfortably be described as classic, and could largely serve as the archetype of public baths in this region of Japan.

When I went in, there were ten or twelve other people already there, a few in the locker room and the rest bathing. Notably, I got a few hellos and not a single look of surprise. I didn’t overhear any remarks about the foreigner who had just arrived, either.

This is good. This is not always the case. At other baths, I have certainly been less than comfortable and have clearly been regarded as an interloper by other patrons, if not with hostility, then at least with deep suspicion.

As a white guy in Japan, I will always be easily identified as an outsider, so it’s always nice when it doesn’t seem to matter.

Another positive: the baths were about as perfect a temperature as could be. This is, again, not always the case. I remember one particular sento in Yokosuka4 that was thoroughly wonderful, almost exactly to my perfect preference, except that the baths verged on unbearably hot. An hour or more after leaving, our hands and feet were still tingling and red.

But at Urawa’s Inari Yu5, the water was perfect. Hot enough to make the cold bath an invigorating contrast, but not so hot that one couldn’t comfortably remain immersed for an extended soak.

My only complaint, really, was an aesthetic one. At most sento, on the wall above the baths, there is usually some sort of mural. In this part of the country, often featuring Mt Fuji. There was no such mural, which is basically fine. Instead of a painting, though, three Mickey Mouse decorations in faded, vacuum-formed plastic were tacked to the wall and spattered with white paint from the last time the interior had been repainted.

Even avid fans of Disney would have to admit that these were incongruous, at very least.

But if that was my biggest (only) complaint, then that’s quite good overall.

When we departed and walked home, I already knew I wanted to go back, soon and often.

It will take time to become a regular there, but I hope to do so. Even on my first visit, it felt uncommonly comfortable, and when a new experience feels so much like home, the best thing to do is to happily run with it.

-

A type of communal bath house in Japan (read more on Wikipedia) ↩︎

-

An interesting concept that describes places other than home and work/school that fulfill certain social functions in community-building (read more on Wikipedia) ↩︎

-

The cost of going to a public bath in Japan varies depending on where you are in the country, and are sometimes subsidized by the local government, as they are largely struggling to stay afloat. Here in Saitama City, the public baths I’ve visited have all had an entry fee of ¥450, the current equivalent of US$3.95 or €3.41. ↩︎

-

Kame no Yu, 亀の湯, literally Turtle’s Bath (View on Google Maps) ↩︎

-

Do give it a visit if you find yourself in Saitama City (View on Google Maps) ↩︎

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email.

And if you like what I’m doing, please consider directly supporting this project for as little as $3/mo on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

#flashnano 2021, Day 1

This November, I’m going to be attempting to fully complete Nancy Stohlman’s FLASHNANO, a monthlong challenge to write a piece of flash fiction every day of the month. This is sort of an alternative approach to NaNoWriMo, which challenges people to turn out a 50,000+ word novel during the month of November.

I’m already pretty busy with writing and basically never write fiction, so this will be a challenge and a stretch, but a challenge and a stretch that I believe I will benefit from.

I can’t claim to expect any of it to be any good, but it’s something that I am confident will help me improve as a writer, and hopefully should be pretty fun, at least some of the time.

And with that, Day 1:

Prompt: Write a story that takes place in the dark

She smelled like soap and her the sweet-smelling perfume he remembered, the aroma now seeming slightly juvenile for her age, but still fit her spirit.

Everyone in the party was in their thirties, but it had somehow morphed into something targeted at resurrecting all the awkwardness and mortification of junior high school, the justifiable embarrassment of it all held at bay with alcohol.

They played spin the bottle. Truth or dare. And now, seven minutes in heaven.

They had been in this situation before, twenty years back in time. They had both been too nervous to manage anything more than a fumbling, dry kiss on chapped lips back then, their physical proximity forced by being in Mindy’s dad’s coat closet, which was still full of coats.

Now it was the walk-in closet in Mindy’s new condo, so there was more space, at least. Even so, the atmosphere was just as overstuffed with the clumsy residual attraction of leftover adolescent crushes, now with a couple of decades worth of self-awareness somehow amplifying the adolescent awkwardness such that it transcended space and time to fill both of them with equal parts butterflies and regret.

In the intervening years, they’d both married and divorced and found themselves again drifting, when most of their friends seemed to consider the shape and course of their lives more or less a settled matter.

They laid silently on the floor, side by side and staring straight up into the featureless darkness, the new carpet springy and itchy under their bare arms and legs. It was hot outside, but the central air made the walk-in closet more like a walk-in freezer.

And who air-conditions a closet? Mindy, apparently.

He cleared his throat to speak, but had nothing to say. She slid her hand over and grasped his gently, warmly. He’d held that hand before, in what seemed like a different lifetime, enough so that it could have been someone else’s memory.

Her hand seemed surprisingly small, until he remembered that the last time he had held it, he’d been more than 30cm shorter and built like a faint pencil drawing of a twig.

She spoke, suddenly.

“I think they forgot about us in here. It’s been a while, hasn’t it?”

“Yeah, I think you’re right. Maybe it’s OK, though. It’s quiet in here. It’s nicer than out there. They never stop talking, do they?”

“Not really, no.”

More quiet. She squeezed his hand.

He didn’t know what to say next, but spoke anyway.

“That party. In eighth grade. I’d never kissed anyone before that.”

“I hadn’t either. Oh god, we were so fucking awkward then.”

“I’m glad that’s all resolved now, aren’t you? The awkwardness. We’re doing so much better now.”

They laughed together and sighed, the tension dissipating. For a little while, they just held hands there, quietly in the darkness.

She rolled over on her side and came close. Eyes open, but unable to see each other, she tried to kiss him and missed, her lips landing on his left cheekbone, just below his eye.

More laughter, briefly, before the second attempt hit its mark. The sort of kiss both of them had hoped for back then but could not achieve, lacking both the courage to go for it and the necessary experience to know what to do.

There are advantages to getting older.

She laid partially across his torso, head on his chest, the top of her head just under his chin. They held each other, contentedly, enjoying both the physical warmth and the human contact that both had gone so long without.

“Let’s just say like this for a while.”

And they did, happily forgotten by the party continuing on without them downstairs.

619 Words

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 86: Falling Into Patterns

It wasn’t the first time I had moved in with a romantic partner, but when I moved into my current apartment with my girlfriend in 2017, it certainly seemed different. For one thing, we were recently engaged. Never had I promised the rest of my life to anyone, so that was new. We were also sincerely happy and actually had a healthy and highly functional relationship. A type of relationship which was (sadly) also a novel experience.

But as wonderfully happy and exciting a time as it was, a great challenge still stood before us. A challenge faced by pretty much every couple in our situation:

Learning to live together.

Cohabitation can be dicey, especially when you’re first figuring out how to incorporate the lifestyles of two recently independent individuals into a new, shared lifestyle that suits both parties.

When you begin living together, suddenly there’s nowhere to hide your idiosyncrasies. You may have done your best to represent yourself honestly and accurately to your partner before that, but once you’re sharing a living space, all is laid bare.

You quickly learn about the minutiae of personal matters, for example. I learned she brushes her teeth longer than I knew was possible. She learned I shower in a very particular sequence, which even I didn’t realize until her presence and observation put a spotlight on it.

Each person learns what the other needs, wants, likes, and dislikes. Peeves and quirks surface and must be accounted for. Boundaries and expectations are established.

Though the need to learn and adjust never really ends, that initial, more intense period of determining how best to cohabitate does naturally subside. And as it does, patterns and habits emerge. These are practical, but also serve as an emergent identity of sorts. The unique fingerprint of a life shared by two people who are trying to make the most of their time together.

These patterns of daily life become a reliable and reassuring framework, something that provides a baseline of normalcy, regardless of what else is going on.

And though some of this might be deliberately established, much of it is naturally fallen into. Patterns that seem to form of their own accord when nobody’s looking.

Most mornings, I make her miso soup, my movements well-practiced and nearly automatic. She vacuums the apartment with the same sort of familiar efficiency. Whoever bathes second washes the bathtub so that it’s clean for the next day. Small things that seem insignificant individually, but together describe an underlying structure of shared life.

Some of it is purely practical, but some patterns of established life together are expressions of care and consideration. These include accommodating alone time and doing some things separately.

One of her greatest pleasures is taking long baths while reading, especially on Sunday evenings. Meanwhile, I like to have a quiet evening walk by myself and to spend quiet time with my thoughts, usually in the park near our home (weather permitting).

And so, on Sunday nights, she takes her long bath and I wander around for a little while. Later on in the evening, we enjoy time together, this made more special by the solo time we had before and the understanding that accommodates it.

Four years in, we’re much better at living together than we were at the start, but are still finding our way. So long as the relationship is healthy, that way-finding should remain ongoing. If it ever stops, we’re in trouble.

It is my sincere hope to still be discovering new and better ways to share our lives for many, many years. Even as our lives enter their final stages, decades hence, I hope to be as glad as I am today to share with my life, home, and happiness.

If I am still contentedly cooking her breakfast forty years from now, I’ll consider that a great personal success in a life well lived.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 85: Absent

I was sitting around with a handful of students yesterday who had arrived early. And in the early afternoon, we received news that a student, a little girl who I had seen just last week, had died.

Her father had called the school, voice shaking, to inform us of the event.

It was sudden. When I last saw her, she was bubbly and full of energy, as she always was. She came in displaying a vitality that is wholly at odds with what has since happened.

Later, as I was preparing for today’s classes, I arranged the magnetic name tags we put on the whiteboard every day. When I got to her name on the list, I was obliged to cross it out.

A thick black line drawn through her name, as she would not be attending.

There is nothing profound or poetic to say about it. We are in shock and cannot tell the other students. We are not sure what to do with ourselves.

It rained heavily all last night.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 84: Conditioning

Ostensibly, I am an English teacher. My students do everything in English at my after-school facility, and we teach a brief lesson in English, in addition to having them do worksheets and read aloud from a series of graded readers.

But really, we’re taking care of the kids for a few hours after school while their parents are at work. We get them to do their homework and make sure that they follow the rules. Strictly follow the rules. This, I would argue, is actually the primary function of my job.

In The Little Red Schoolbook from 1969, authors Søren Hansen and Jesper Jenson wrote to the book’s intended audience of children:

Instead of helping you develop as an individual, schools have to teach you the things our economic system needs you to know. They have to teach you to obey authority rather than to question things, just as the exam system encourages you to conform, not to be an individual.

So it was in the late nineteen sixties in Denmark, so it remains in much of the world in 2021, perhaps especially in Japan. This is readily apparent. And while I do not deny it for an instant, I do take exception to being party to it.

So I quietly resist every single day.

Everyone demands things of them, but not enough people encourage them to be curious or to be true to who they are. Almost nobody gives them permission, let alone a push, to question authority or to push against the structures to which they find themselves subject but from which they rarely benefit.

While I make sure they follow the rules that matter, not all the rules matter. I try to minimize their busy work, too, and give them what free time I can. It’s when they are free to do what they want that you see their identities come through in the greatest clarity. This is when they are able to be themselves.

When in play, they reveal the amazing people they are at heart, unabashedly exhibiting the personality and character at risk of being walled off in the name of conformity and fitting into a society with specific expectations of them. Expectations that require a sacrifice of the individuality and creativity that we are all born with, but that only a tragic minority of us actually get to keep into adulthood.

I’m worried about these kids of mine, but I know my position is limited. Still, it is my responsibility to do for them what little I can. I believe in them and care about their futures, and I am worried. Every day, I try to be an honest and trustworthy adult in their lives.

I wish there were more I could do.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 83: Bulging

The forty-liter clear plastic bag bulged and looked ready to burst, its surface stretched taut like the skin of a drum over the contours of its irregular contents. Brown scabs of packing tape mended it in several places, holding it together and preventing it from further splitting where sharp edges had ruptured the thin polyethylene.

It was like this every week. The bag of plastic recycling comically large and overstuffed to bursting, like a farcical suitcase. Only instead of personal belongings, it contained the rinsed plastic trays and wrappers from another week of eating almost exclusively from the convenience store and the ready-to-eat section of the supermarket.

Most of the containers never held anything particularly good or nutritious or even interesting. Instead, their value was derived from a combination of affordability and availability.

Most important was that they were what could still be bought after work, when everything was already picked over at the lone supermarket that was still open, where a loose, bleary-eyed crowd of office workers shuffled listlessly behind the clerk with the printer that spat out discount stickers. Freshly stickered packages were snapped up immediately, regardless of what they contained.

It was not uncommon to see some bedraggled customer pick up a package of food and stare at it blankly for an extended period, their expressionlessness a reflection of their inner state as they tried to remember what it was they were meant to be thinking about.

A five or ten percent discount never did much to improve the taste of limp, wet pasta salad and couldn’t remedy the texture of fried foods long since congealed in the refrigerator case. All the little yellow stickers really did was to save you a few yen in the course of making an easier job of selecting a sad dinner from a sad array of options.

Back at home, supposed staple foods aged into retirement in the refrigerator instead of being used, all while the recycling built up like this every week. I wanted to cook. I liked cooking. But after every split shift, there was neither sufficient energy nor spirit left to accommodate even the most basic cooking.

It was a tremendously imbalanced lifestyle, as further evidenced by the bag of aluminum cans that grew in tandem with the plastics. The cans were a mix of empties formerly containing black coffee, energy drinks, and canned highballs. Evidence of the endless cycle of alternately chasing wakefulness and sleep, never getting enough of one before the clock said it was time to switch to pursuing the other.

Some weeks, those bags seemed to take up as much space in that tiny apartment as I did. Two sullen companions sulking quietly as they crouched on either side of my garbage can.

Every Tuesday night, I took out the recycling, usually late at night so I wouldn’t have to remember in the morning before work. As I carried it down from the second floor, the bag of plastics crinkled and popped loudly, while the cans clanked and buckled as they bumped against my legs. All of these sounds were amplified greatly in my head by my desire, equally awkward and intense, not to disturb my neighbors.

When I returned to the apartment, my living space felt slightly but palpably more spacious. This lasted for a couple of days and was a highly valued sensation in a life that featured precious little slack or breathing room.

Nothing seemed to change much back then, not for a long time. My kitchen drying rack was more often filled with freshly rinsed food trays than with actual dishes, and my spare time more often filled with solo activities than with anything social.

That was years ago now, and while my recycling bag still fills up, it’s with the packaging from cooking for two, and it’s been a long, long time since I last followed a supermarket clerk, waiting on discount stickers to be applied to food I didn’t really want.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email.

And if you like what I’m doing, please consider directly supporting this project for as little as $3/mo on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 82: Hidden Away

It was either the wind or the cat and, between the two, it seemed more likely to have been the cat. The big spider plant wasn’t sitting on the upturned bucket as it usually was, with its dozens of green tendrils cascading toward the floor. Instead, it was mostly upside down on the balcony. The terracotta pot had broken into several large sections, one of them having fallen away, revealing a network of greenish-white roots packed so densely that no soil was visible.

A year or so earlier, I had re-potted it to give it more room to grow. It responded enthusiastically. And though I knew that its many offshoots were a sign of diminishing space, I had no idea the extent to which it had grown below the surface.

Plants are good at that, at keeping secrets subterranean and contained.

Humans are less adept at hiding things, despite our supposed intellect. We get distracted and careless. We leave clues, sometimes despite our best efforts, but also sometimes half hoping to be discovered. Secrets are unceremoniously revealed sometimes, when circumstances are just different enough from normal daily life to seem separate and safe. And in other times still, evidence of a secret pops up by itself in surprising places, having been separated from the person to which it belonged, now free to drift independently through the world.

There was my well-dressed neighbor who always left his home with practiced, efficient movements at the door meant to minimize the chances of anyone seeing inside his home, lest they glimpse his overflowing hoardings that threatened to spill out into the street with every opening of the door.

There was the man on one train in Tokyo whose white button-down shirt was tucked into his underwear. It would have been easy to attribute to sleepy carelessness alone, had it not been for the presence of black, ruffled satin and a garter belt. It had also happened on more than one occasion.

There was the young father with his two small children at the public bath, who was cheerful and smiled sincerely as he engaged in locker-room banter. And who, upon disrobing, revealed extensive, beautifully detailed tattoos stretching continuously from his elbows to his knees, everything about them indicating an affiliation with organized crime, and everything about them leading to the friendly banter drying up.

And finally, who could forget the forlorn, homemade sex toy that once occupied a corner of a local parking lot for a surprisingly long time?

Clues are everywhere. Everyone leaves them, whether or not a secret is even consciously being kept. Past-due bills on bright paper peeking out of a poorly closed kitchen drawer, a stack of romance novels spilling out of a notably prudish acquaintance’s closet, fresh injection marks on the arm of a friend who claims to be clean.

We’ll never been as good as plants when it comes to keeping things hidden, and that’s OK. Plants only do it by accident, and they have no need for secrecy. We’re apt to mess up, flawed as we are, and are better off with fewer secrets, anyway.

So as I repotted the spider plant in a suitably large new terracotta container, burying those amazing roots and once again hiding them from view, I had to consider what little I had in my life that was secret, and what I might do if something came along and shattered the shroud that kept it hidden.

Better to phase out secrets entirely, I thought. I’m no plant, after all, and no matter what I might try to keep buried, or how much effort I might devote to the task, it’s bound to resurface eventually, anyway.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email.

And if you like what I’m doing, please consider directly supporting this project for as little as $3/mo on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 81: Capsule Elegy

Tokyo is about losing one of its most iconic buildings. Its fate now sealed, the Nakagin Capsule Tower, with its parallel stacks of tiny pieds-à-terre in capsule form, will disappear from Ginza, where it has stood since nineteen seventy-two.

It is instantly recognizable. It looks like nothing else. And it will undoubtedly be replaced by something with neither characteristic.

Its detractors often seem to see it as an eyesore, revealing an allergy to visionary design on their part, or at very least an intolerance of healthy variety.

They also readily point to something that is sadly very true: it is in poor condition and getting worse.

Unfortunately, the future that architect Kisho Kurokawa envisioned for his mold-shattering masterpiece is not the future it got, and now, forty-nine years later, it stands there with the clock counting down to zero.

Despite its practical failings, it remains highly successful as a design. Even in its current state of disrepair, it embodies an ethos and remains suffused with the confident optimism, enthusiasm, and clarity of vision that brought it into being in the first place. Few buildings ever manage to command such remarkable presence, and many that do lose their edge as the rest of architecture catches up around them.

In this case, the field never closed the gap.

If only these things were enough to keep it around another half century or more. But they are not. All is lost, or would be if it were not for a feature of the design itself.

The structure was originally erected in just thirty days, this being made possible by its modular design. All one hundred forty capsules were manufactured off site and trucked in, ready to be lifted by crane and installed.

It was meant to be renewable—evergreen in a way that never materialized. The concept of hot-swappable living units remains compelling, but never came to be. Even so, this innovation has proven to be of value in the end, as the capsules will be removed before the rest of the building is torn down. Many will be refurbished and given new roles at new locations.

So, while the iconic building as we know it today will soon be gone, much of what comprises it will survive to see a new phase of existence. The Nakagin Capsule Tower will assume a new, distributed form.

It’s not ideal, as architectural preservation goes, but at least it’s something. Not bad, one supposes, given the circumstances, and better than losing it entirely.

The locations of the capsules will necessarily change and multiply, as will the views from the circular windows at the end of each capsule, and one wonders what stories these new chapters will tell.

It’s hard to say what the future holds, but it’s worth remembering that, even when you don’t really want to go, sometimes a change of scenery ends up being quite nice in the end. Especially when the alternative is total annihilation.

Somewhere in Japan’s main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email.

And if you like what I’m doing, please consider directly supporting this project for as little as $3/mo on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 80: The Old Life

People in Japan still commonly use kerosene space heaters in their homes. Enough so that, in the winter months, kerosene trucks drive slowly through neighborhoods in the evening, making their presence known with a repeating announcement played over a loudspeaker, accompanied by the tune of an old children’s song.

Before I quit working in Tokyo, I had Fridays off, and during the first winter we lived together, I would go off wandering on Friday afternoons before buying groceries for dinner, departing around the time the sun was getting low and golden. It back-lit the fog of my breath as I walked, growing fainter before disappearing, the light leaving the sky and the clear, deep black of the winter night bleeding heavily into the rich blue of dusk.

On nearly every one of these walks, I encountered a kerosene truck at least once.

And while the western sky retained a modicum of glow, I would step into the Life, an old neighborhood grocery store with a visibly graying customer base.

Going inside wasn’t quite like stepping back in time, but did give a certain impression of age. Something akin to entering an alternate present that carried a powerful influence from the world of several decades before. The space itself gave this impression, overriding the fact that the products on the shelves were all contemporary.

The ceiling was relatively low, and the space below it was lit with humming, gently flickering fluorescent bulbs that painted everything with an enfeebled, green-tinged glow. The patrons were strikingly pallid, thus illuminated, and when lamps went bad, odd corners of the shop took on a hushed, quasi-dormant atmosphere in the shadows.

The floor tiles were well-deteriorated in places, a dark gray material showing through where the pattern had long since been worn away, with ever-deepening depressions formed by decades of foot traffic. Near the registers, even the concrete subfloor peeked through here and there, burnished to a shine.

In odd, inaccessible nooks near the ceiling behind refrigerator cases, dust drifted like snow.

Just as entering that space gave the impression of entering a slight vacuum where time didn’t add up quite the same, the moment of leaving after shopping was one flooded with sound, sky, and air. A sudden return to regularly scheduled programming.

Stepping back out into the night, I headed for home with my groceries, the tune from the kerosene truck still playing softly somewhere off in the distance.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email.

And if you like what I’m doing, please consider directly supporting this project for as little as $3/mo on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 79: Transmitter

When I visit the local shrine, it is not an act of religious devotion, though it might look that way. When I throw my coin, bow twice, clap twice, and speak, it is simply an act of existing as a human in the world, in the honest state of not knowing how existence works, humbly accepting my smallness in the very bigness of it all.

I know neither how the greater universe operates nor the significance of this life. Or my place within it, for that matter. These things are both unknown and unknowable, and that is fine.

In the context of universal infinite immensity, the shrine is vanishingly small. We as humans even more so. In visiting the shrine, I seek to bridge the gulf between small and large, to open up and momentarily touch boundlessness.

Saying a prayer at the shrine has, to me, a distinct and profound significance. Stepping up to the saisen bako1 on the steps of the shrine feels like stepping up to a microphone wired to a celestial transmitter. There, I can speak my small-t truth into the greater, big-t Truth of all existence.

If or where or by whom prayers may be heard, or if they are heard at all, I do not know. The significance of the act is in the sending, like throwing bottled messages overboard into the sparking waters of the cosmos. They are not addressed, nor are they meant for any given recipient. I have no control over where they may wind up, or by what route they might arrive. It is possible that they will never arrive anywhere at all, drifting forever towards the horizon of being, while that horizon simultaneously and endlessly recedes. This, or any other outcome, is perfectly fine.

It is, to me, about the grounding gesture of surrendering to something much greater than myself and saying what needs to be said in the moment, in the manner that seems correct. I am able to speak what I need to speak, to transmit the things I need to express, and after one final bow, am able to depart the shrine and walk home with the road feeling ever-so-slightly more substantial beneath my feet for having broadcast my honest truth.

-

A wooden chest with a grated top found at shrines and temples where one throws coins as offerings ↩︎

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 78: A Different Model

The street running past my apartment building has no name. This is neither a fluke nor uncommon. Most roads in the area, and in fact most roads in Japan, aren’t named.

Those that have names generally have (or had) some sort of special significance, such as the old Nakasendo, a nearby historical route connecting Kyoto and Tokyo. It’s been around since Kyoto was the capital city and Tokyo was still called Edo.

Given the general dearth of street names, a question arises—how do addresses work? A natural question if you’re used to addresses depending on street names and numbers. There’s a system to it, though it may be perplexing at first. I didn’t really understand it until I moved to Tokyo and had to figure it out.

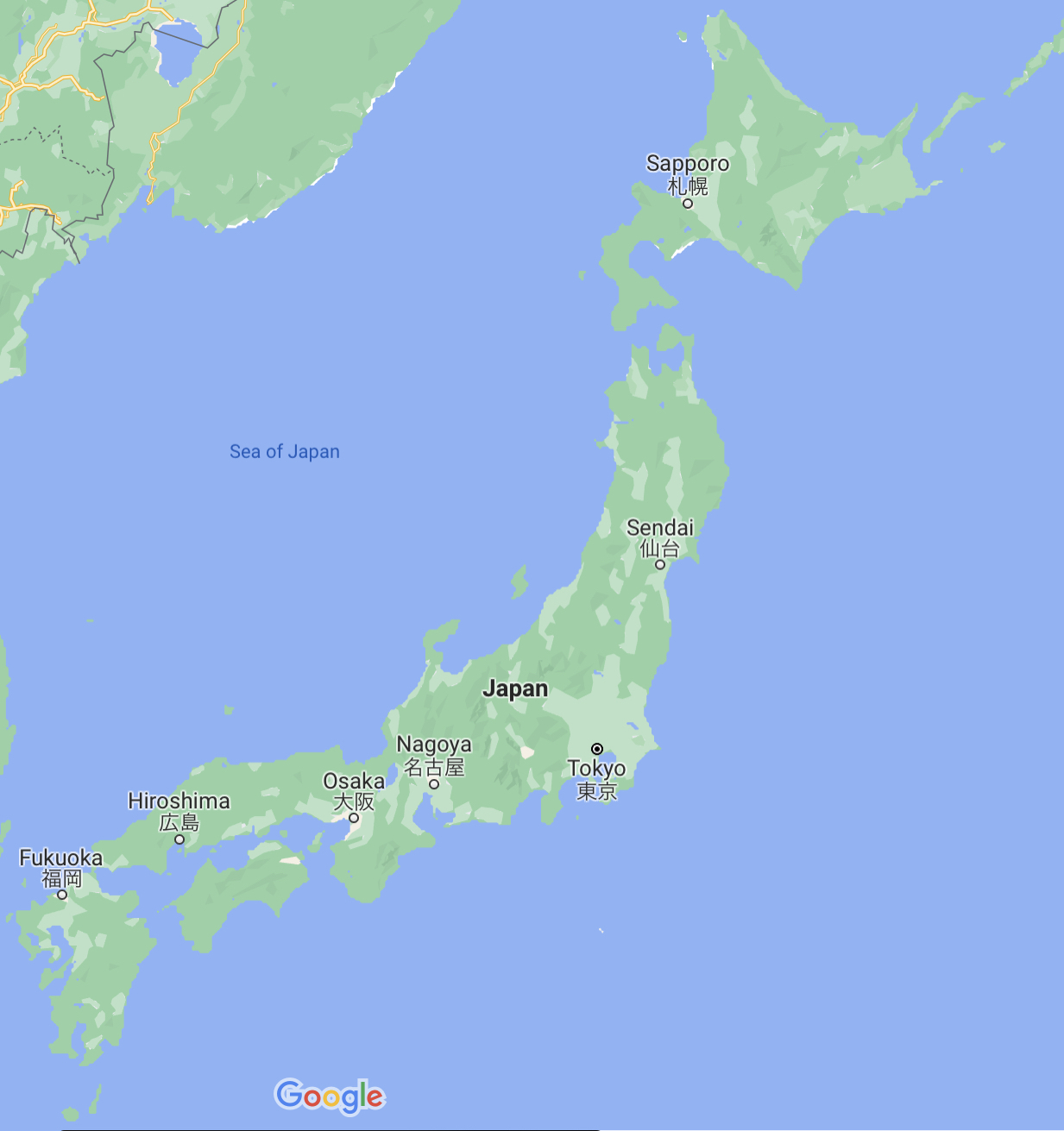

In Japan, addresses work like a set of nested circles, with each subsequent part representing a section of the area preceding it.

Let’s look at an address as an example.

〒330-0064 埼玉県さいたま市浦和区岸町7丁目10−23

330-0064 (postal code), Saitama Prefecture, Saitama City, Urawa Ward, Kishi town/neighborhood, district 7, block 10, building 23

Within Japan, first you’ve got the prefecture, then the city in the prefecture, then the ward within the city, and so-on all the way down to the building number, and even the unit or apartment number (if applicable).

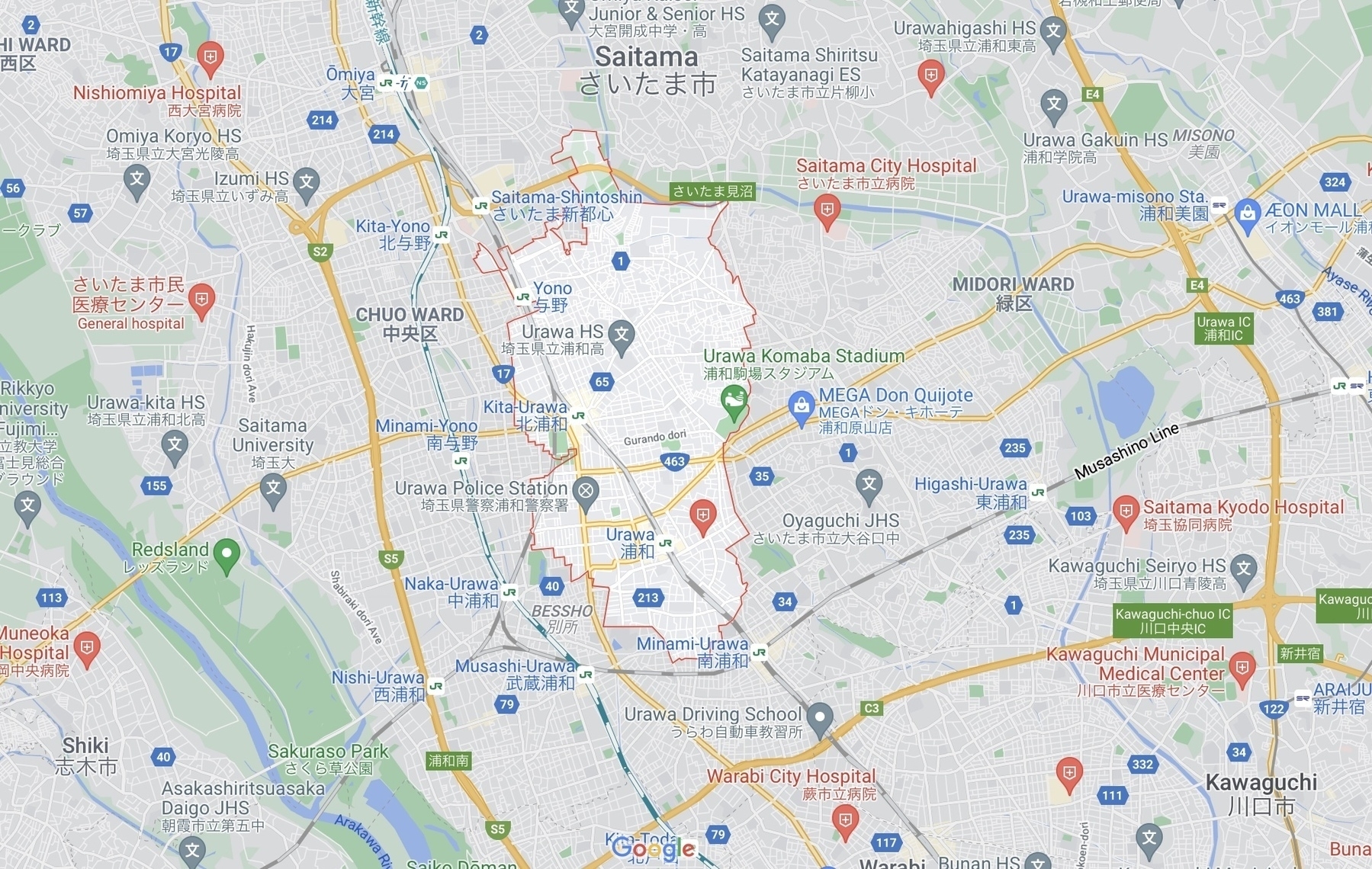

Let’s look at it visually. First, Japan:

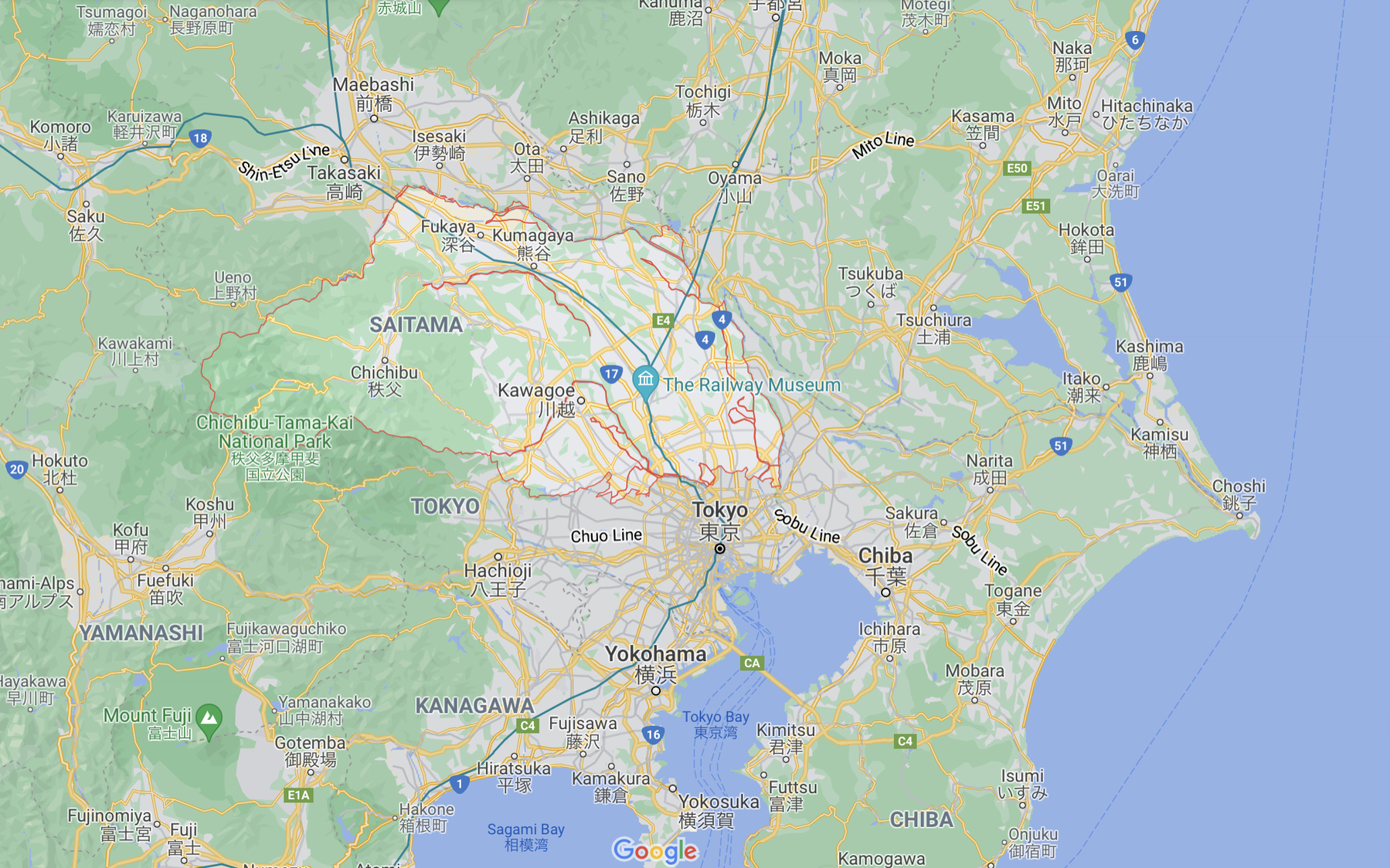

Second: Saitama Prefecture

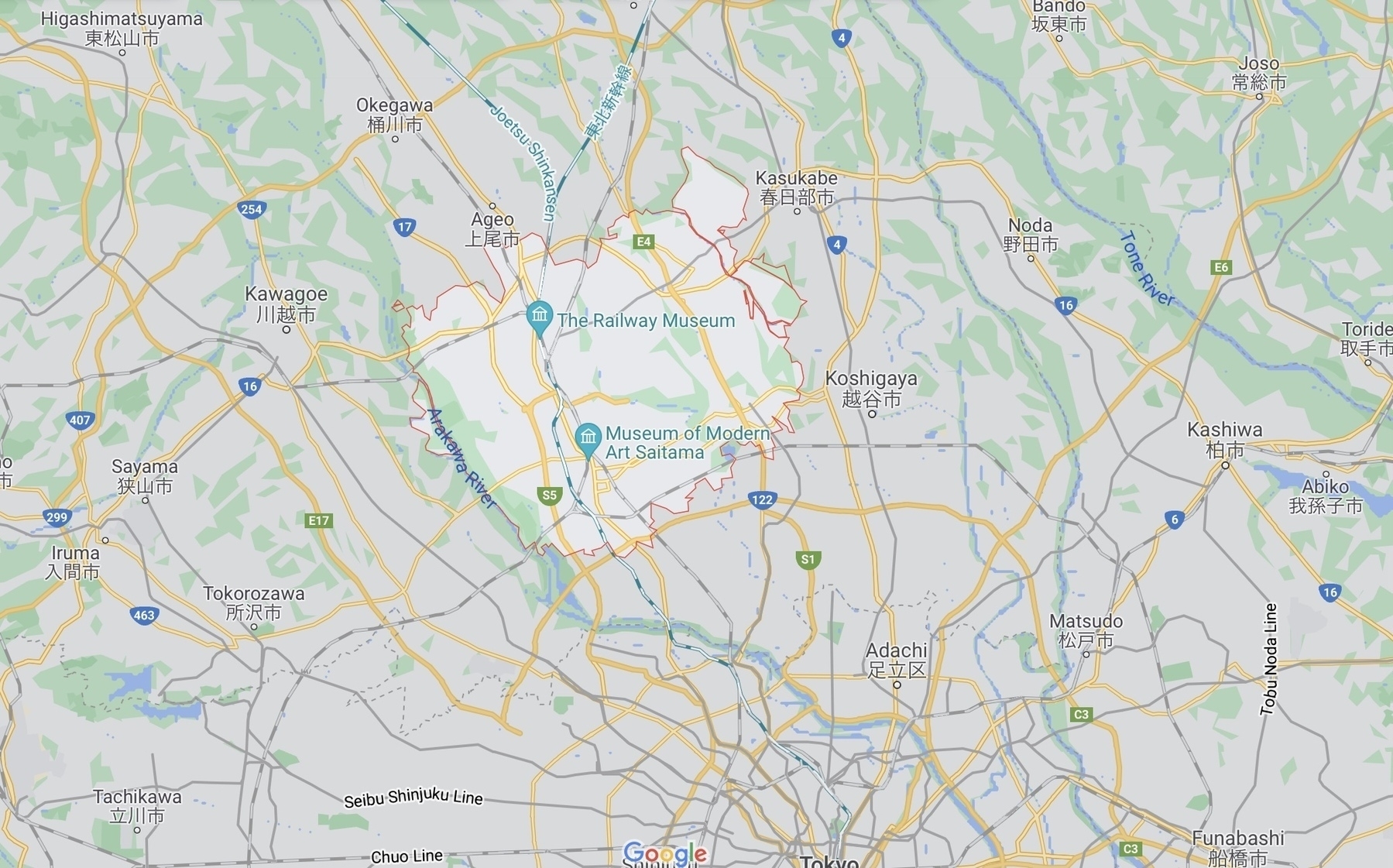

Third: Saitama City

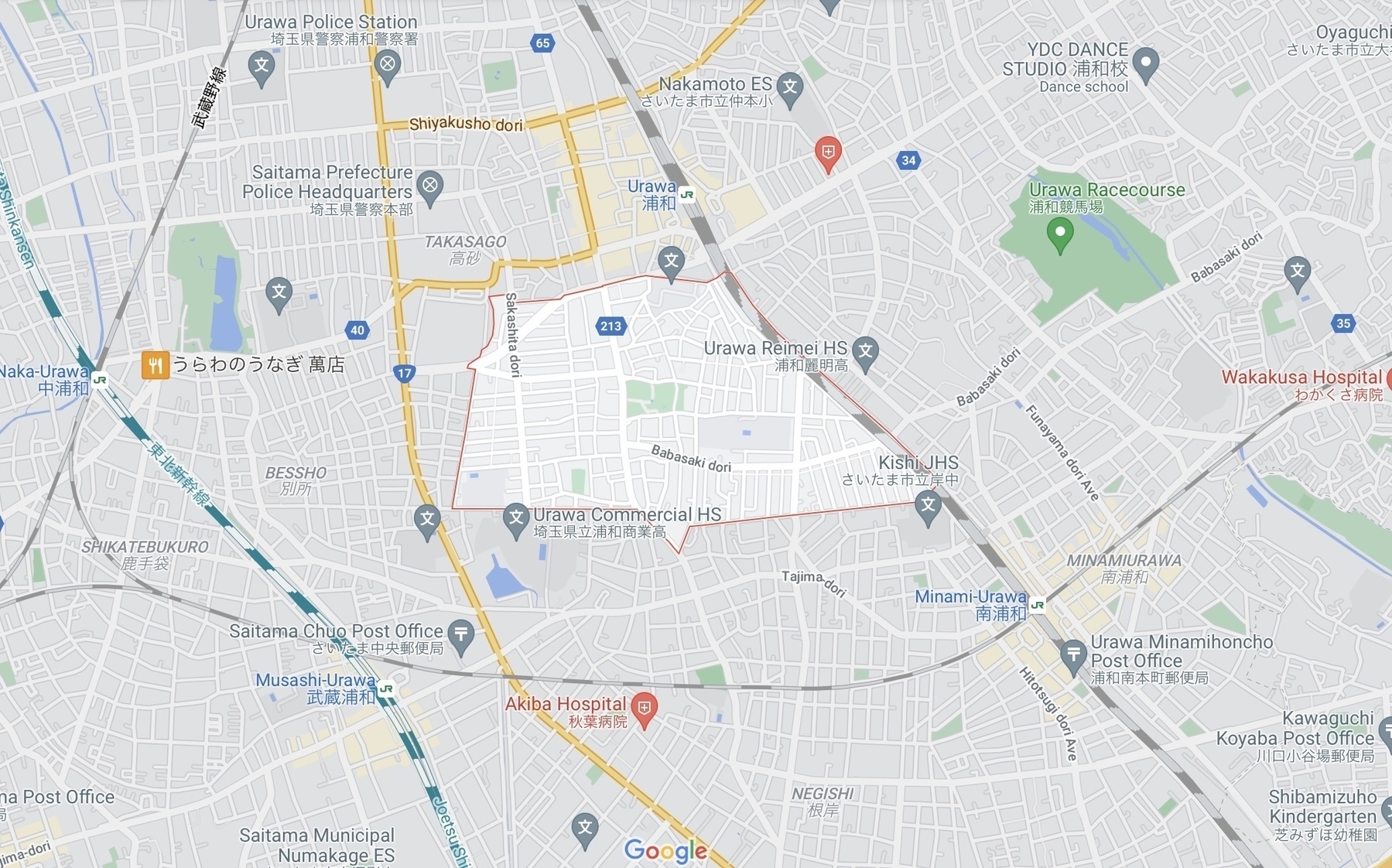

Fourth: Urawa Ward

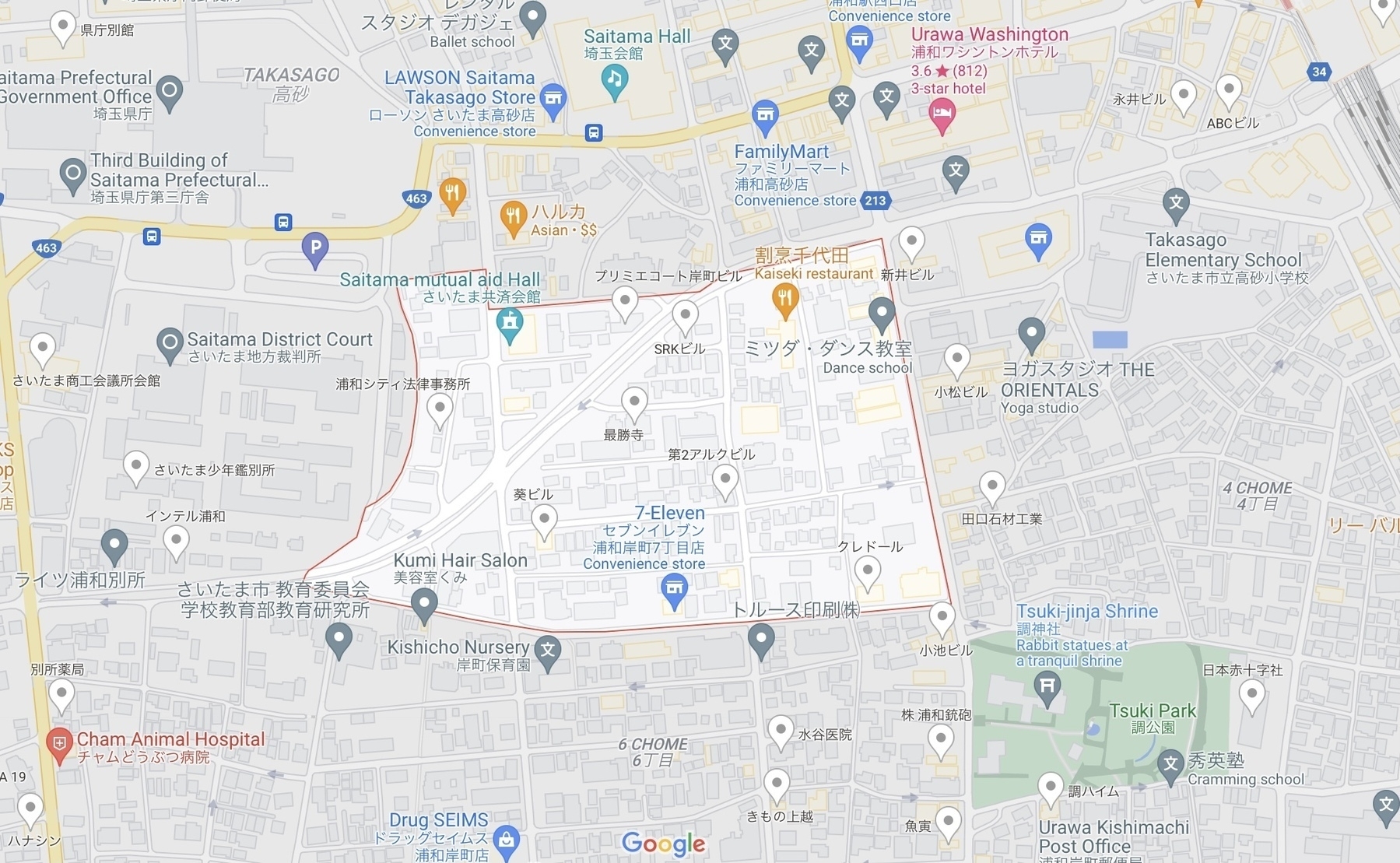

Fifth: Kishi neighborhood

Sixth: District 7

Seventh: Block 10

Eighth: Building 23

Which puts us at a nearby 7-Eleven.

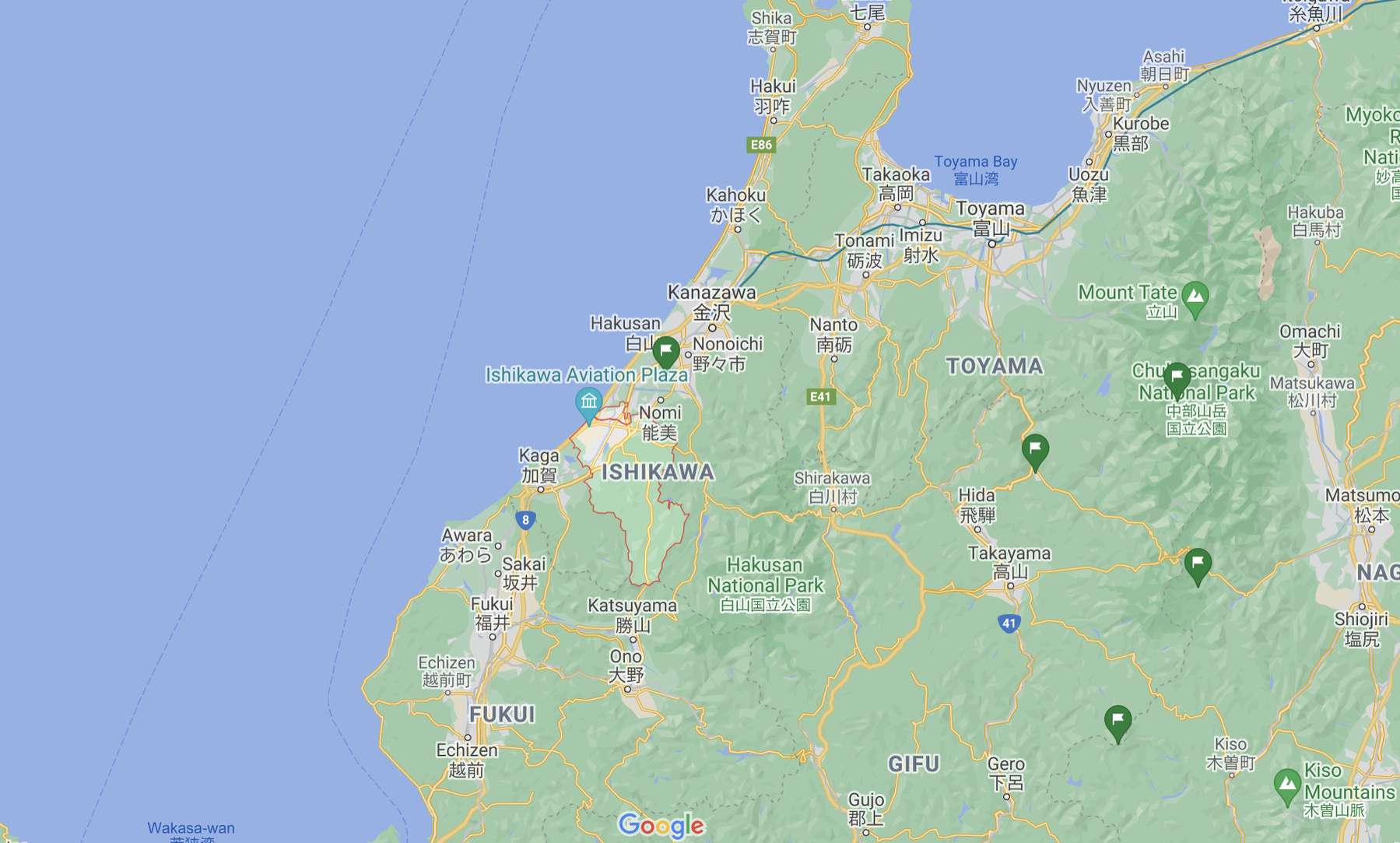

Of course, being in a large city in an even larger metropolitan area, this is a complex and particularly specific address. Elsewhere in Japan, you might find an address that’s notably simpler. Let’s take, for example, the location of a random soba shop in Ishikawa Prefecture. The address is simply:

〒923-0186 石川県小松市大杉町手打ちそばもとや

923-0186 Ishikawa Prefecture, Komatsu City, Osugi Town, Motoya Handmade Soba

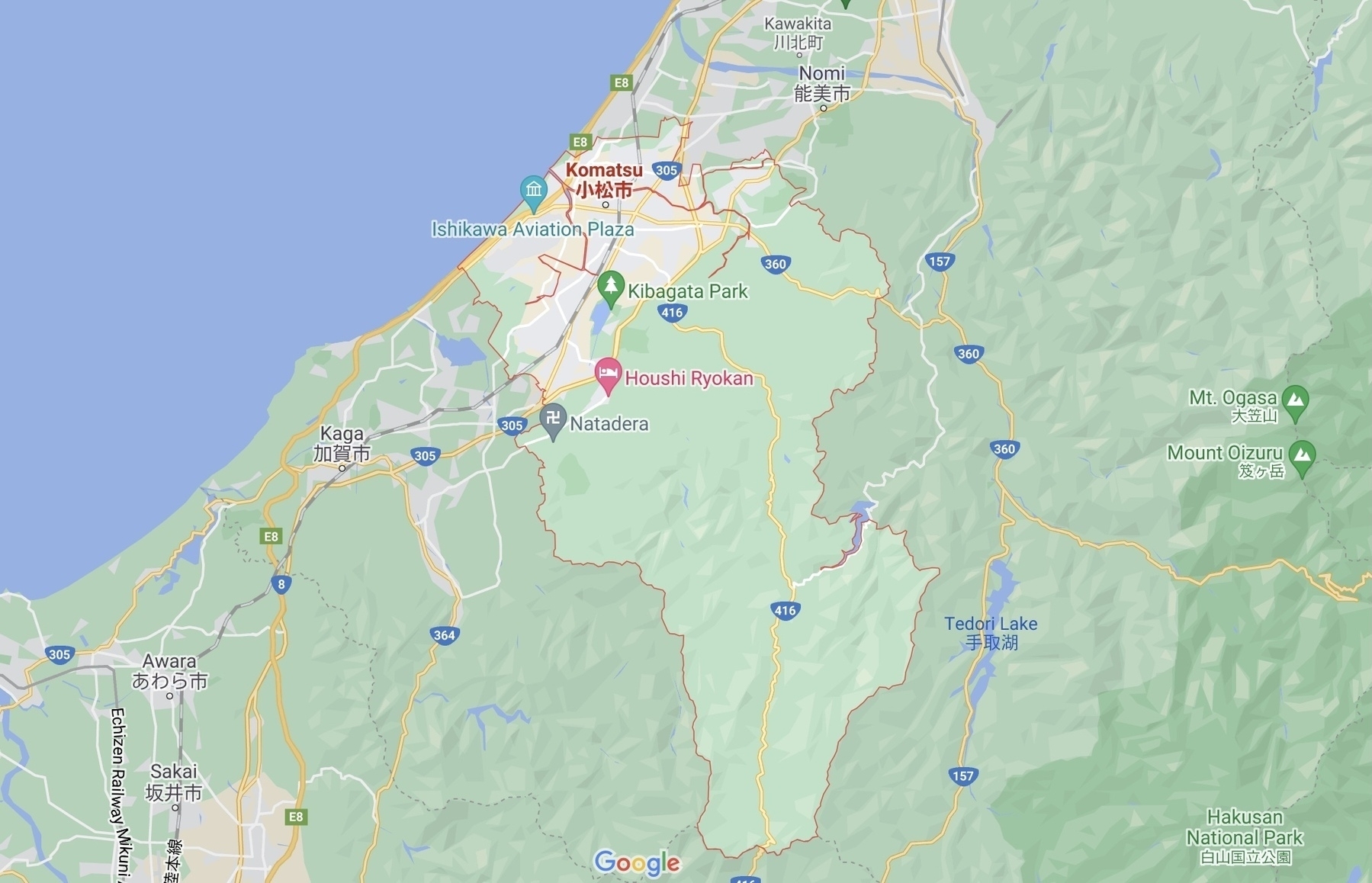

Ishikawa Prefecture:

Komatsu City:

Osugi:

The Osugi area includes a fair amount of land, but there isn’t much in it. By adding the business name—in this case Motoya Handmade Soba—you’ve got all the specificity you need for the post office or navigation app to know where it is. Besides, districts and wards and block numbers don’t exactly mean much when the area looks like this:

As unfamiliar as the Japanese address system might initially be and as confusing as it might initially seem, it’s pretty logical. Of course, it doesn’t help you much if you don’t have a map to consult or extensive knowledge of an area already in your head, but that’s true of most address systems.

I’ve seen some people call it weird or strange, but that’s not a fair assessment. In life, both abroad and in general, it is often useful to ask if the things that strike us as odd are actually odd, or if they’re just unfamiliar. Is it weird or just different? Almost always, the latter is the answer, and either way it’s an opportunity to learn something new.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email.

And if you like what I’m doing, please consider directly supporting this project for as little as $3/mo on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 77: Blemished

Perfection is a dull proposition. It represents a fool’s errand in human pursuits and is as about as common as hen’s teeth in nature. And, even if you can find something in the natural world that seems sufficiently close to perfect to be labelled as such, how much can the experience of it really give you?

Consider a perfectly colored, apparently flawless autumn leaf. It is delicate, gracefully proportioned, and blazed in the brightest crimson. It is impeccably beautiful.

It also lacks much depth beyond that initial impression. The only story it really has to tell is that nothing much ever happened to it. It’s the story of a charmed life that is devoid of anything noteworthy.

If you’ve seen one perfect leaf, you’ve seen them all.

If you look closely at a more average leaf, though, blemished and scarred by the unpredictable events of the spring and summer, you can partake of its unique character. This is a non-transferrable experience. What you observe about that particular leaf applies to none other.

Colors may form irregularly, perhaps interrupted by insect or damage. There may be tears and pieces may be missing. It may have sat and dried into a curious shape. It may be yellow and green on one edge and orange on the opposite side.

The especially flawed and peculiar leaves among the autumn foliage have a particular depth and beauty to them. They hide nothing, telling their story with unashamed candor. They have so much to say you if only you approach them with a frame of mind suited to receiving their message.

It’s not that you shouldn’t appreciate the perfect leaves among the imperfect majority. You absolutely should. But once you’ve done so, spend some time considering the more ragged among them, appreciating their eccentric beauty, as well as their captivating tales.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email.

And if you like what I’m doing, please consider directly supporting this project for as little as $3/mo on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 76: Truncated

It had been a beautiful, mature zelkova tree. It had a high canopy that spread beautifully over one corner of the park like an immense, lush green parasol. It provided habitat, shelter, and shade, and the pleasing noise of its thousands of leaves whispering together in the breeze saturated the air.

That is, until its patulous limbs were unceremoniously eliminated.

Last year, a tree-cutting crew from the city showed up and started work. For a few days I thought they were going to remove the tree entirely, along with two neighboring, similarly lovely trees.

Fortunately, they did not, though what they did do was scarcely better, amputating every branch and leaving the trees to start over as sorrowful, fifteen-meter stumps.

Now, nearly a year later, they are fringed with sad tufts of leaves on tiny new branches.

What is the point of allowing trees to mature beautifully over decades only to cut them back so violently? So contemptuously?

The presence of trees is a gift, in the city especially so, but clearly not everyone sees it that way. Some seem to take them as a burden, something loathsome better pruned mercilessly than cared for with any amount of sincere concern.

I used to spend hours reading and writing on a bench under those trees. It was such a pleasant place to be, and in the summer it was notably cooler in that deep shade than in the direct sun nearby. This, in addition to all the other joys of sitting under the boughs of a wonderfully large tree. Even just staring up into the branches was a joy, watching the sky sparkle through shifting gaps in the foliage.

Now the sun finds no impediment, no barrier to keep it from that corner of the park. The draw of that place has been replaced with a sad bitterness that rises every time I see those great, heavy trunks now topped with what little new growth the trees managed in the last year.

And I know that, ten years on, they may look a bit more like their old selves again, with shade being cast in a slightly larger radius from the trunk with every passing summer. But it seems so much easier, so much more compassionate and benevolent, to simply accommodate a mature tree’s calm presence than to disdainfully penalize it for existing, abusing a great and beautiful organism for no good reason, to the benefit of absolutely no one.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can be awesome and support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 75: Fleeting Escape

We’d have been fools not to take hold of it and run. An errant fragment of summer that turned up in the wake of a typhoon. We stole away with it, taking the train two prefectures over and setting up shop on a stretch of sand fringed with driftwood.

Sand below us, water in front of us, the great mountain sitting huge in the blue haze to our right.

For several hours, she rested in the shade of our shelter, stretched languidly on a blanket in her floral sun dress, feet toward the surf and head turned toward the curious dreams that come with a head cradled in sun-warmed sand and the salted breeze wafting crashing waves and the calls of hungry crows.

I wandered for hours, watching clams bury themselves and wading into the sea up to my neck. The water was more cool than warm, but pleasantly so, like a cold shower in August, when the tap water has warmed somewhat with the ground.

Fish jumped all around me, in such a way that I could imagine something larger, some predator that they were trying to evade, weaving between my ankles as a coyote might weave between trees in pursuit of a rabbit.

The air was warm but not hot. Warm enough to enjoy, but not so much to deny the changing season. The sun shone with the searing sparkle of summer, but only just briefly.

When she arose, we walked up and down the sand together, talking and looking at everything. We felt certain in the wisdom of our having come.

The sun, which had been near its zenith upon our arrival, was steadily lowering itself toward the horizon. In time, it sank below distant peaks and the great mountain cast its shadow up into the atmosphere, hanging there in the sky until it subsided into the dilute pastels of twilight, the moon rising brilliantly in the west.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can be awesome and support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 74: Loud as Flowers

The highway is quiet, and small sounds seem loud. The traffic on National Route 298, elevated over my right shoulder, is only faintly audible, reduced to a relative whisper by its height and enclosing barriers.

Louder than the highway are my narrow bicycle tires rolling on the wet asphalt, the road turned jet black and sparkling by the rain. Vibrations reverberate and sing through the wheels as the rubber leaves fleeting tracks on the vitreous pavement.

Louder are the sounds from the long string of parks under the highway. The footfalls of a jogger, cinders crunching rhythmically underfoot. Someone clattering a chain-link fence with a soccer ball. Two friends talking and laughing, happy and tired, sitting at the edge of a poorly lit basketball court.

Louder are the commuter trains passing at a distance and the door chime of a nearby convenience store. Louder is the tomcat in the auto shop’s parking lot.

Loudest of all, though, are the osmanthus blossoms, projecting their redolence into the night with such thunderous aromatic intensity as to overwhelm the conventional sensory borders and flood territories inaccessible to lesser scents.

Their heady aroma gives the moist air a palpable thickness and heft, such that you feel you are swimming in a saturated, soporific concoction of apricot, honey, and hypnagogia, with undercurrents of the autumn sun’s penetrating warmth.

Deep lungfuls bring it through your nose and mouth simultaneously, forming flavors that recall adolescent arousal and the heart-pounding memory of holding someone close for the very first time, the residual tatters of lust and limerence from an earlier life mostly forgotten.

It invades and invigorates every sense. It textures the world and tingles the skin. It sparkles the vision, echoes the soundscape, and floods the mouth with nectar.

The mind licks its teeth and thirsts to drink this overwhelming atmosphere of tiny golden flowers wafting their siren song on the breeze. And on nights like this, with a light rain amplifying every olfactory perception, you can easily lose yourself in it for prolonged moments.

But the moments, however long they feel, remain just moments all the same, no matter how much all of our senses conspire, straining and writhing in unison to prolong the sweet intoxication. And eventually, inevitably, the wind shifts, the blossoms fall, and their brief season of salacious jubilance concludes.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can be awesome and support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 72: For a Limited Time

The air smells of dry leaves and the subtly spiced, slightly sweet aroma that escapes them as they decay. From within the leaf litter and from every tussock and thicket, soft stridulations waft like lithe wisps of wood smoke on the gentle evening breeze, the crickets calling tenderly under the waxing crescent moon.

Their easy manner and moderation stand in marked contrast to the riotous abandon of the cicadas of just a few weeks ago. They filled every August afternoon with a great noise, delivered with an intensity befitting the season’s powerful heat. They have not yet disappeared entirely, but are fading quickly, and soon the season’s last cicada will sing to an empty room.

But while the summer’s insect voices are fading to silence, the autumn chorus is building with a soft determination in the underbrush. And as we pay attention to the crickets on quiet autumn evenings, listening attentively to their tremulous calls in this, their own short season of prominence, we may guess that the significance of these sounds extends well beyond what we, as humans, can understand.

These insects have lives to which we can relate in only the most abstract of terms. Their existence is almost entirely alien to us.

Take lifespan, for example. Most species of cricket only live two or three months, which means that, on average, most humans will outlive your typical cricket by a factor of at least three hundred and fifty.

We can’t really grasp a life so brief, and if we try to imagine our own lives scaled down to just ten weeks in length, it becomes absurd. You’d hit puberty about twelve days after birth, graduate from university about ten days later, and arrive at retirement age with just a few days left to live at nine and a half weeks.

Of course, a cricket’s life and a human’s life have precious little in common, so admittedly it’s not the most useful comparison, but its value lies in reminding us how little we really know and understand in this world. It reminds us to appreciate the fleeting nature of life, and to consider that there is so much that we cannot directly perceive, but that is still very present and real.

These early autumn crickets will die off before the year is over, and we will know no more about them and their habits by then than we do now. What we can do for them, at very least, is to appreciate them while they’re here, as they sing from the undergrowth and remind us through their own ephemerality that, though we have more time here than they, our stay is every bit as limited.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can be awesome and support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 71: Troublesome Gaps

The word shotengai1 refers to a traditional shopping street or district, commonly with a roof covering the primary thoroughfare. Written 商店街2, the three characters translated literally mean merchant shopping street. They are typically lined with a variety of shops and stalls, from clothing stores and houseware shops to greengrocers, izakayas3, and stationery shops.

They are still a common feature of many towns and neighborhoods in Japan. Our weekend outings often specifically include visiting such places, sometimes with the intent to shop, but always with the intent to explore. Some of them are still very busy and important local centers of activity, while many others are clearly on the decline, with many shuttered storefronts and any future economic revival unlikely.

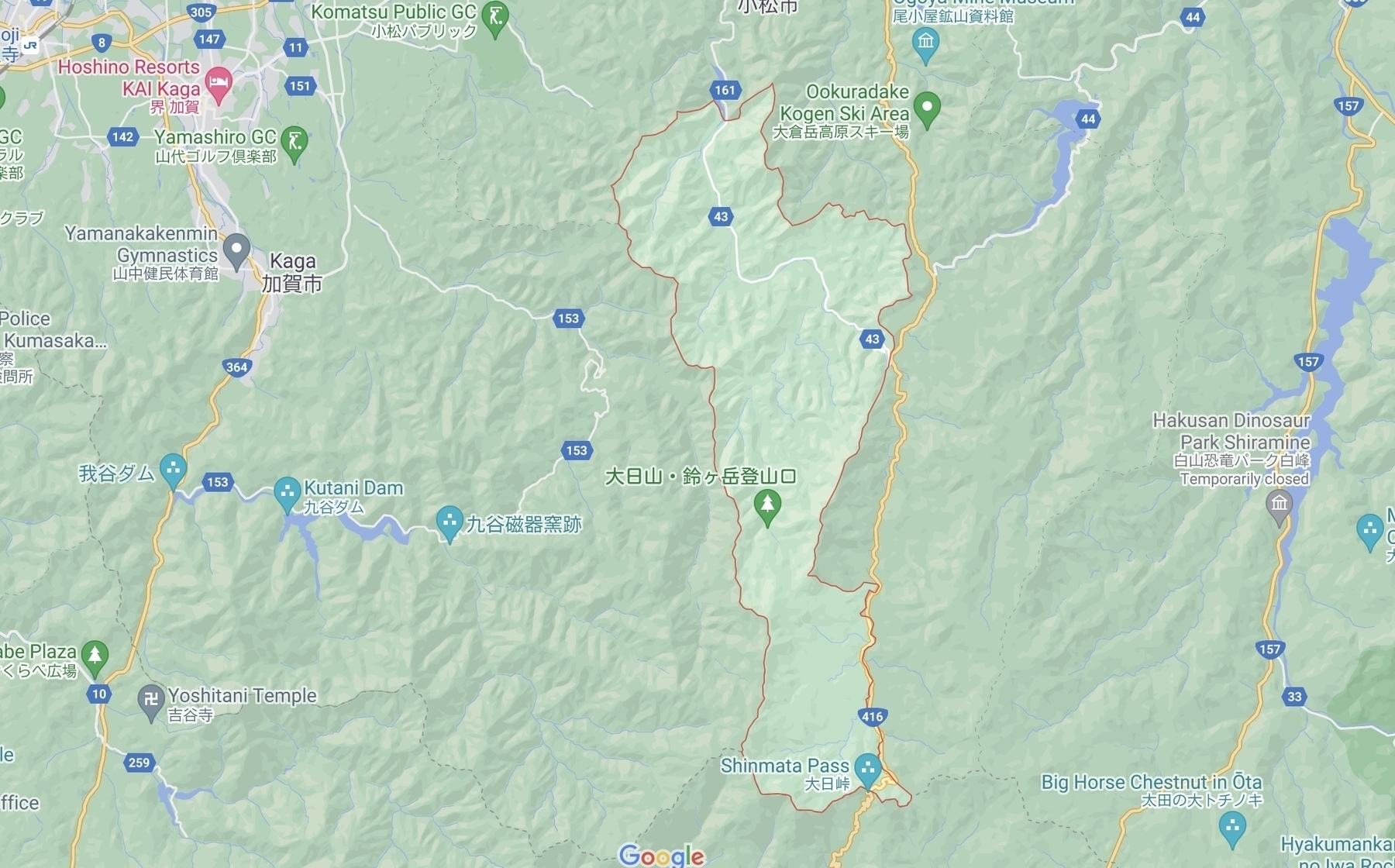

Last weekend we visited Jujo4, an area in northern Tokyo near to the border with Saitama. Our official mission for the day was to buy miso paste, which we try to purchase exclusively from a wonderful miso shop there. It sits at the end of Jujo Ginza, the local shotengai, where we always spend a while wandering around, seeing what we can see and seeking out what has changed since we were last there.

Our last visit was about three months before, and as always, there were a number of visible changes. There is always at least a shop or two that disappears, with new tenants taking their place, and this visit yielded no exception.

Somewhat troubling, however, was the number of buildings that had gone missing over the last few months. In at least four places, large, airy gaps now exist where storefronts previously stood. One showed signs of new construction, but the others simply sat vacant, the ground covered with great swaths of black fabric.

One wonders how long they will remain like that. While it is entirely possible that, by the time we visit again, new buildings and businesses will occupy those spaces, it is also possible that they will remain empty for a long while. This often happens in Tokyo I sincerely hope that those gaps are soon filled, however, and that Jujo Ginza retains the vitality that so many other shotengai have lost.

Somewhere in Japan’s main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can be awesome and support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

-

Shotengai on Wikipedia: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sh%C5%8Dtengai ↩︎

-

View entry on jisho.org for 商店街 at https://jisho.org/search/%E5%95%86%E5%BA%97%E8%A1%97 ↩︎

-

The usual Japanese casual eating/drinking establishmentshttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Izakaya?wprov=sfti1 ↩︎

-

An area I like in Tokyo: on Wikipedia, on Google Maps ↩︎

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 70: Rainfall

The uniformity of the steady rain’s sound does not hold up under close scrutiny. Though comprised of a very specific (some would say narrow) range of smaller sounds, they remain distinguishably distinct.

Greatest among the differentiating factors is that of the surface upon which the rain lands, drops of rain like tiny hands striking the skins of myriad drums.

The metal deck of the balcony. Potted plants placed thereupon. In the garden just beyond, various trees, and each type of foliage leading the rain to produce a distinct sound—a palm frond differing from clusters of pine needles or the broad leaf of a paulownia, for example.

Then there’s the swath of textile covering the ground behind the building to keep weeds at bay, and the small concrete pad at the edge of the lot. In the neighbor’s driveways, cars lend their surfaces.

The rooves of different buildings, as well, from the flat tar roof above me, to the ceramic tile on one neighbor’s house, to the corrugated steel on another.

The longer you focus on it, the greater the detail and variation that becomes apparent.

With my eyes closed, I lie still in bed, listening intently. It is still dark, and the alarm won’t go off for three and a half hours more.

I will go back to sleep soon. This won’t be hard. The first days of September have brought weather cool enough to feel cozy in, and a steady drizzle to play the part of a waterlogged lullaby. I try to hear as many of its details as I can before the soft, velvet darkness of sleep once again enfolds me and the soft patter of the rain dissolves into nothing.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can be awesome and support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

New things are in the works, including a podcast version of all posts from the blog. Additionally, an occasional (hopefully weekly) patron-only behind-the-scenes podcast feed on Patreon.

Somewhere in Japan Dispatch № 67: Continuity

35°40’10.79"N, 139° 44’ 52.89"E

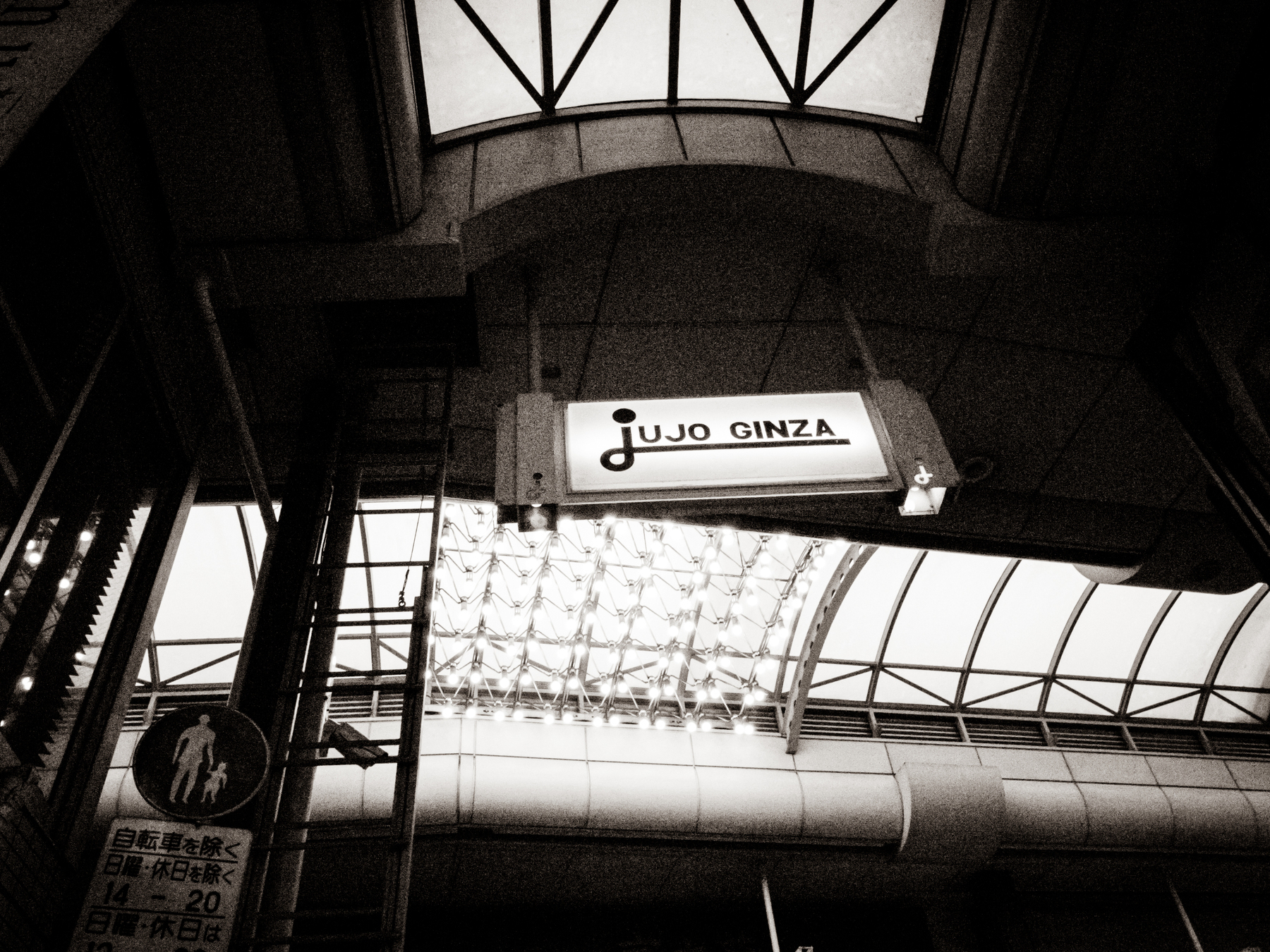

Surrounded on all sides. Hemmed in and dwarfed by glass-clad towers and blocky office buildings, all of them seemingly monuments to a specific disinterest in any form of architectural creativity. Nestled in the middle of all of this, in a section of Tokyo that seems designed to eradicate any hope within any office worker who might have once entertained a fantasy of leaving the corporate world behind, is a shrine.

Kotohira-gu has been in this place since 1679. At that time, the city was still called Edo, and wouldn’t be renamed to Tokyo for another 189 years, when it became the capital of Japan. It had already come a long way from its origin as a fishing village on an estuary, and it would only be another forty-two years before Edo’s population reached one million.

It has stood there in what is now Toranomon for 342 years. Much has happened. Lots of good, yes, but for a moment, let us consider some of of the bad.

The shrine was there in 1703 for the Genroku earthquake, with an epicenter not far away, and the subsequent tsunami. The wave, along with the earthquake, claimed as many as ten thousand lives. In 1792, the Great Unzen Disaster killed another fifteen thousand.

It was there in 1828 when the Siebold typhoon took more than nineteen thousand.

It was there during the Great Tenpo Famine from 1833 to 1837. And it was there when, in 1896, the Sanriku earthquake generated two tsunami that reached over thirty-eight meters in height and killed more than twenty-two thousand.

It was there in 1923 for the Great Kanto Earthquake, when over a hundred thousand lives were lost.

It was there for the first and second Sino-Japanese Wars, the Russo-Japanese War, and the Second World War, during which the shrine stood as long as it was able until it was destroyed1. It stood, in whole or in part, during the firebombing of Tokyo, when more than a hundred thousand perished, and months later when the atomic bombs fell and took a quarter million. In total, WWII resulted in more than three million Japanese deaths, nearly a third of them civilians.

It was there on March 20, 1995 when, less than 500m away, members of the Aum Shinrikyo cult released sarin nerve agent in the subway, targeting Kasumigaseki and Nagatacho stations. Fourteen died and more than five thousand were injured.

It was there during the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, which most readers will have memory of, having happened a scant decade ago. Nearly sixteen thousand died then.

And it is there, today, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The death toll is poised to exceed that of the 2011 event any day now, if it hasn’t already.

Millions of tragic deaths over hundreds of years. Human suffering stretching to the horizon and beyond. But time, of course, continues on, and so does everyone who survives.

Nothing lasts forever, good or bad, and there is something to be said for looking at the things that connect us to the past, to a time long before we were born, and consider the struggle and tragedy that befell so many before us. Struggles and tragedy that were very real, but struggles and tragedy that nonetheless eventually passed.

The way things are can seem unending, the awful pull of eternity lengthening perception in direct proportion to suffering. This is where many of us are today, especially as it hits home that this isn’t over. That it isn’t really even winding down yet—only just changing.

But when you go and stand somewhere like Kotohira-gu, it is grounding. It is peaceful there, and it is beautiful. It is a lovely place to visit, perhaps to pray, and to feel connected to a reality that extends beyond our current circumstances. This, despite the incongruity of its present setting and the desperate facts of the day.

It has been there for more than a dozen generations, and it may remain there for at least that much longer still. Chances are, it will outlast every single person alive today. This is, I would argue, not a morbid resignation to fate, but instead a comforting reminder that, in time, we will emerge from this.

-

The shrine was rebuilt following the war in 1951 ↩︎

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can be awesome and support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 65: I Am a Visitor Here

It looks like I’m having lunch with a friend, there on the 45th floor, at a table by the window with a sweeping view of the Tokyo sprawl that stretches out until the haze marries the ground to the sky. And though I am enjoying myself, I am not here for fun. I am working. This is an English lesson.

In my bag, the clothes I wore when I came into the city. In the muggy August heat, the only way to arrive at the restaurant not totally drenched in sweat is to bring extra clothes and change after I am safely in the dry chill of the hotel’s air conditioning.

The most challenging part of this work is keeping under wraps how out of place I sometimes feel in these settings. It’s fun, sure, and the food is good, but if I weren’t with a client, I doubt I would ever find myself in such places.

Places like a teppanyaki steak restaurant frequented by famous actors. An elite private dining club with a hidden entrance. Hostess bars with achingly beautiful women who smile and are nice to me because it’s their job. And in each case, I’m there working, too, though the only real clue that’s visible to others is the small notepad always at hand, filled with new vocabulary, expressions, and grammar notes.

These situations make me feel slightly on edge. And it’s not quite that I feel like an imposter. No, I can make pleasant enough conversation with the people I meet, and I can appreciate the food and wine as much as anyone else. Even the hostess bars can be fun, once it’s established that I’d rather hear about their Pomeranians or how grad school is going than have them feign amusement at my forced, nervous jokes.

It’s something else. The sense of being an interloper, briefly transiting through a sphere that is not my own. Not a fish out of water, but a fish temporarily in the wrong body of water. I’m a trout in a tide pool.

And while it’s fun to be immersed in these other worlds, these places are not for me. It is mentally exhausting, and it is always a relief to return home to my ridiculous cat, to my humble apartment, and to the beautiful woman there who smiles and is nice to me because she loves me.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can be awesome and support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 64: No Plan, Best Plan

At about 8 o’clock in the morning, we decided the beach was out. Door to sand, it takes us at least two hours to get there, and on a day that threatened to be mostly rain, along with multiple typhoons in the area that could make the surf unswimmably high, we decided with a small sense of defeat to stay closer to home.

We didn’t have an alternate plan and didn’t make one. We had some small errands to run, and we figured would just wing it once those were done. Winging it tends to yield good results.

After stopping at the post office, we went to the station and boarded a train, still with no particular plan. We’d gone several stops by the time we decided to get off at Higashi Tokorozawa and walk from there to Niiza. We had spotted an extensive park from the train, and that was enough.

We followed the train tracks and meandered through quiet residential streets, then rested at a beautiful hilltop shrine that stood on the former site of a castle that had overlooked the area nearly five hundred years before.

Nearby, the park. It was large, with a lotus pond and shady, overgrown margins. A trail led up a hill, the trailhead marked with warning signs for mamushi, a small pit viper endemic to Japan.

The hillside was densely wooded, the trail in deep shade, with deciduous trees on one side and bamboo on the other. The wind, the residual fragments of the passing typhoon, bending branches and stalks halfway to the ground, rustling every leaf, the sound of it all combining into an unbelievable static, to which was added a spooky knocking of bamboo on a bamboo, the sound of which is something in between the ringing of bells and the hammering of wood. On top of it all was the combined song of innumerable cicadas, singing for mates, so many insect sounds layered and mixed that the din of it cancelled out thought. On that dark trail, the noise of it all leading the mind into a peaceful emptiness.

We lingered there for a time, suspended in the moment, before continuing on, enjoying the snails and mushrooms in the undergrowth, the swaying of the forest canopy, and the trickling of a hillside stream. After emerging back into the sun-drenched expanse of the park’s green center, we felt renewed.

That evening, we agreed that our time in the forest, relatively brief though it was, had been the highlight of the day.

It was a great day together, and all of it had been made possible by not having a plan. We did not know what we wanted to do, except that we wanted to go somewhere. We decided everything in the moment based on a gut feeling. It was one of the most enjoyable days we have shared in our years of wandering together, made possible by following the best, most reliable plan of action I know—having no plan at all.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can be awesome and support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 63: No Return

There are expressions, the original meanings of which may differ from what they end up meaning to us personally. Following the posthumous publication of the Thomas Wolfe novel of the same title in 1940, the expression you can’t go home again entered the public consciousness, and has been interpreted variously ever since.

As best I understand it, Wolfe meant it in the sense that, if we try to return to the place we have long remembered as home, especially if it’s bathed bathed in the golden light of nostalgia, the reality and the memory will never mesh. That remembered place is ultimately only accessible only in the imagination. If ever it truly existed as remembered, it no longer does.

The expression often has a different significance, though, for those who emigrate from their home countries and remain abroad for an extended period. I don’t mean the people who go abroad on a lark, backpacking around Europe for a gap year or spending a bit of time teaching English on some other continent. No, I mean the people for whom being away from their place of origin has become the state that is more familiar, maybe even more comfortable.

Part of the trouble is the very concept of home, which becomes so dilute and nebulous for many, sometimes even before going abroad. In the USA, for example, I lived in eleven eleven in six states, and then lived in five different cities in four Asian countries. I have lived at twenty-two addresses in the last thirty-nine years. It gets to be a bit much.

The already-slippery concept eventually all but entirely lost its meaning after years as an emigrant and only regained some of its significance years after settling in Japan.

At this point, the idea of home is most strongly associated with where I live now, with my partner, where I am building a life, and no longer has any sincere connection with where I came from. This new significance exists only because of the deliberate decision on my part to redefine the concept to fit what I needed it to be. No longer a matter of origin, but instead of a sense of belonging and being where I most want to be.

There is also the simple fact that the longer you remain away, the more a person is changed by the experience. The long-term wanderer becomes like a warped and misshapen puzzle piece, no longer able to fit into its original designated place, and incapable of reverting to its original form.

You no longer think the way you did before moving abroad. You become a fundamentally different person. And sure, you can go back and visit familiar people and places, but you’ve become a square peg to that round hole.

Another difficulty is how the physical and relational distance changes how you connect (or not) with the people from your former life. More true than absence making the heart grow fonder in this case is out of sight, out of mind. The longer you remain away, the greater the personal distance grows.

Friendships and family relations alike become less vibrant and active, fading and often eventually dissolving entirely. Not out of any ill will, but just because you’re no longer there. After a while, you tends not to hear much from old friends, or even from family members unless we make a particular effort to keep communications active.

The long-term implications are different for everyone, I suppose. Some people may simply drift indefinitely, never redefining home for themselves in a way that allows them to reclaim it, and unable to build anew the kinds of relationships that can fill the void left by those that have been lost. This is the emotional equivalent of being stateless. It is a lonely place to exist.

I would also say that it’s unnecessary. You can choose, instead, to claim a new place and circumstance as home, investing your time and energy in building the relationships and structures that give home its significance. It isn’t easy, but worth it.

So maybe you can’t go home again, in that you can’t return to what was. But you can claim a new home for yourself, and then you don’t have to worry about whether or not you can go back. You’re already there.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can be awesome and support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 62: The Bike of Theseus

Most adults seem to have forgotten what all kids know with certainty: a bicycle is a tool of personal freedom, an implement of liberty. Want to go? Just go. Get on and roll. No license necessary, nor gasoline, nor keys for the ignition.

Got legs? Got a bike? You’re good to go.

Not long after I moved to Japan, my friend Yohei invited me up to Saitama, where we built a bike for me out of a frame and other parts he had lying around. He knew I loved riding and that I needed a bike of my own. It was an ugly duckling—functional, though a strange jumble of everything.

But it was a bike, and it was mine. A ticket to personal mobility and a way to get out of my apartment and get out of my head.

I’m still riding it, though all that’s left of the original bike now is the frame, and that’s likely to go in the next year. Every other part on the bike has since been replaced.

From day one, it’s been my bike. At the ugly duckling stage as well as now, when it falls more easily into the category of finely tuned machine. And though in the foreseeable future not a single part of the original bike will remain, it will still be the same bike to me.

As Heraclitus noted, a person can’t stand in the same river twice. The river changes from one moment to the next, as does the person. But the river remains the same river in terms of identity, just as the person is still who they are and get just as wet.

And I suppose it’s fitting that the bike has evolved as it has over the last six years, and is on the verge of having had every piece replaced. I’ve changed as well, in very big ways, and am attempting to further renovate my Self. But no matter how much I change, I’m still me, and I’m always happy to get on that bike and ride.

Somewhere in Japan, Dispatch № 61: But Only Just

Thirty minutes after sunrise, still half dark. Snow just barely not sleet, wavering in that decision. It falls from a dull, featureless sky hanging over a thousand-year-old temple, and is blown at an angle by a moderately gusting wind.

It doesn’t come down in individual flakes, but in sloppy wet clumps, already partly melted by the time they land in slushy splashes, leaving crystals in wet splatters on every surface.

It falls on the ceramic tiles covering the temple roof, meltwater trickling to the eaves and flowing down to the ground on the kusari-doi, chain gutters hanging languidly from the corners of the eaves.

It falls on the massive weeping cherry tree in the courtyard, and on the adjacent white stone bridge that spans the gravel of the dry garden.

It falls on stone statues with both facial features and inscriptions worn indecipherable by centuries of exposure to the elements. It falls into the water that’s collected in the oval depression carved into the plinth at their feet, where coins are left as offerings.

It falls on the boulder to the right of the entrance, with its deep hollow always filled with water and always holding an arrangement of flowers, no matter the day, the season, or the weather. It falls on the white flowers and red berries, their vibrancy and color whispering vitality into one small corner of a somber and listless morning.

It falls on everything, on every surface. It is quiet enough that the sound of it landing dominates the atmosphere. A melancholy static. Not quite the patter of rain, not yet the soughing of snow.

When the temperature drops another couple of degrees, it becomes more resolutely snow, though just a flurry, and can barely stick on the wet ground. This will be the only snow of the year.

Somewhere in Japan's main home on the web is at somewherein.jp, where you can also sign up to receive these posts by email. And now, for just $3/mo you can be awesome and support this project on Patreon. Click here to learn more.

Additionally, this post’s featured photo is available as a print in its original color version in my print shop. Use code “get30” for 30% off at checkout.